Now that interest rates are rising with much further to go, the global banking system faces a crisis on a scale like no other in history. Central banks loaded with financial securities acquired through QE face growing losses, and their balance sheet liabilities are now significantly greater than their assets—a condition which in the private sector is termed bankruptcy. They will need to be recapitalized urgently to retain credibility.

Furthermore, banking regulators have made a prodigious error in their oversight of the commercial banking system by focusing almost solely on bank balance sheet liquidity as the principal determinant of risk exposure. And on the few occasions in the past when they have demanded banks increase their own capital, it has always been through the creation of preference shares and pseudo-equities to avoid diluting the true shareholders. The consequence is that the level of leverage for common equity shareholders in the global systemically important banks has risen to stratospheric levels.

The regulators may be comfortable with their liquidity approach, but they have ignored the periodic certainty of a contraction in bank credit and the consequences for banks’ equity interests. Meanwhile, G-SIBs have asset to common equity ratios often more than fifty times, with some in the eurozone over seventy. It is hardly surprising that most G-SIBs are valued in the equity markets at substantial discounts to book value.

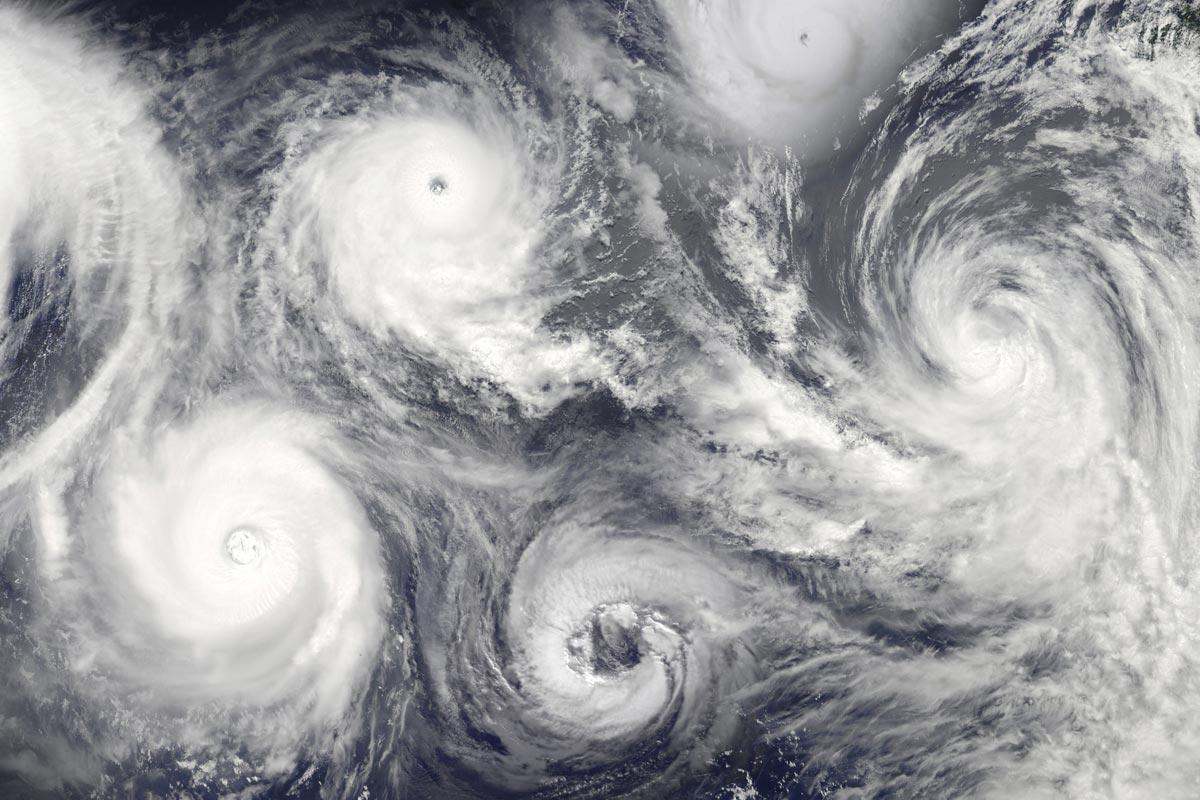

G-SIBs have accumulated excessive exposure to financial assets, both on-balance sheet and as loan collateral. With vicious bear markets now evident and further interest rate rises guaranteed by falling purchasing powers for currencies, the one thing regulators have not allowed for is now happening: like a deepening meteorological low, bank credit is contracting into a perfect storm.

Jamie Dimon’s recent warning that his bank (JPMorgan Chase) faces hurricane conditions confirms the timing. Central banks, bankrupt in all but name, will be tasked with rescuing entire commercial banking networks, bankrupted by a collapse in bank credit.

Why Are Markets Crashing?

It is becoming clear that financial assets are in a bear market, driven by persistent rises in producer inputs and consumer prices, which in turn are pushing interest rates and bond yields higher. So far, investors have been reluctant to lose trust in their central banks which have been instrumental in supporting financial markets. But this is now being tested, more so in the summer months as global food shortages develop.

We have increasing evidence that bank credit is either contracting or on the verge of doing so. This was the message loud and clear from Jamie Dimon’s recent description of economic conditions being raised from storm to hurricane force, and his follow up comments about what JPMorgan Chase was doing about it. Rarely do we get the dollar-world’s most senior banker giving us such a clear heads-up on a change in lending policies, which we know will be shared by all his competitors. And the fact that the bank’s senior economist was tasked with rowing back on Dimon’s statement indicates that the Fed, or perhaps Dimon’s colleagues, know that he should not have made public their greatest fears.

Contracting bank credit always ends in a crisis of some sort. With a long-term average of ten years, this cycle of bank credit has been exceptionally long in the tooth. Before we even consider the specific factors behind a withdrawal of credit, we can assume that the longer the period of credit expansion that precedes it, the greater the slump in economic activity that follows.

Not only is this the culmination of a cyclical bank credit expansion, but it is of a larger trend set in motion in the mid-eighties. Following the inflationary seventies, which was book-ended with the abandonment of the Bretton Woods Agreement and Paul Volcker’s 20 percent prime rates, a means had to be devised to ensure that fiat currencies would be stabilized in a lower interest rate environment. By ensuring demand for dollars would always be sufficient to maintain its purchasing power, then all other currencies that were loosely pegged to it would be similarly able to retain purchasing power without the prop of high interest rates.

Consciously or unconsciously, the planners deployed a variation on the Triffin dilemma. Robert Triffin was an economist who in the 1960s pointed out that a reserve currency would have to ensure that there is sufficient supply of it for it to fulfil the reserve currency role. He concluded that the supplier of the reserve currency would have to run irresponsible short-term monetary policies to ensure the supply is made available, for the likely detriment of long-term monetary and economic prospects.

In the mid-eighties the planners put in place the mechanism for creating Triffin’s demand for the dollar. Deficits would be run by the US government, as Triffin had explained, and dollar bank credit would be expanded. The creation of bank credit outside the US banking system would be permitted in the form of the Eurodollar market. And the growth of shadow banking went unhampered.

Major banks were encouraged to buy into brokers, eventually absorbing them into their operations completely. London’s big-bang was what this was all about, followed by the Glass-Steagall Act being rescinded to allow the American money-center banks to enter brokerage and investment banking activities in their domestic markets as well as offshore. The purpose of financializing the dollar was to ensure there would always be speculative and portfolio demand for it.

The policy has fundamentally overturned the way free markets behave, making them increasingly driven by central bank interest rate policies instead of by non-financial factors. Time preference became progressively less important relative to Fed policy. Whenever the dollar slipped, by lowering interest rates instead of raising them the Fed could encourage foreign portfolio buying. Lower interest rates increased flows of currency and credit into financial assets instead of debasing the currency in the non-financial economy.

It has not been a perfect system, because prices of goods and services still increased reflecting the expansion of currency and credit, but at a slower pace than one might have expected, given the increased quantity of circulating media. Furthermore, calculation methods applied to consumer price indices all had the effect of reducing the apparent pace of price increases. And it was in everyone’s interest to buy into this perpetual system of wealth creation.

Thus, the creation of extra bank credit was directed increasingly into financial speculation in bond and equity markets. There were bubbles, such as the dotcoms in the late-1990s and in mortgage financing preceding the financial crisis of 2008/09. Despite these interruptions, the US authorities made sure that global investment flows primarily supported US financial interests. Thus, the wealth effect was created in America, and consequently through the internationalization of valuations in the jurisdictions of its major allies. And to the extent that credit expansion drove up financial asset prices, the effect was mostly ring-fenced within the financial economy, and was not recorded in official consumer price indices.

As markets caught on, interest rates declined to the point where they disappeared altogether. But as Triffin observed, policies to ensure that a currency is available as the world’s reserve are economically destructive in the long run, and the whole trend set in motion from London’s big bang onwards has now concluded with rising interest rates. It amounts to a super cycle of bank credit expansion certain to end more dramatically than a single cycle. Therefore, this bear market and its systemic issues can be expected to be of a greater magnitude than those which followed the dotcoms and the Lehman failure.

With interest rates so far beneath the rate at which prices are rising, which is mainly the consequence of earlier monetary debasement, losses are now accumulating for all those who bought into the financialization story and have failed to bail out of it. Top of a hubristic list are the central banks themselves which augmented monetary expansion with the acquisition of substantial bond portfolios through quantitative easing. Those assets are now collapsing in value, wiping out central bank equity many times over. The central banks themselves will need recapitalizing before they can tackle the problems of a widespread systemic collapse in the commercial banking network.

With a perfect storm forming in financial markets and the banks, we are witnessing the end of a global economic system which has denied the realities of free markets ever since President Hoover believed that the US Government could improve and then save the American economy in 1929. His errors were magnified by the neo-Keynesians’ hero, Franklin Roosevelt with his New Deal. A Second World War and post-war socialization of capital with a minimized gold standard followed. Every failure has been met with a new doubling down on capitalism.

And every failure has increased the power of the state over its people and diminished their freedom. The drift away from a world of progress, where people were free to exchange the fruits of their labor with the intermediation of sound money, enabling them to succeed or fail by their own efforts, has led to the ultimate failure: a looming collapse of the whole statist system.

Since the last fig-leaf of gold convertibility was finally abandoned fifty-one years ago, the final phase of our decline has been covered up by the increasing financialization of western economies, substituting paper wealth for real prosperity. The function of fiat currency has been to perpetuate this illusion, an illusion that is finally coming to an end.

In the financial and economic violence which we now face, it is difficult to anticipate the order of a series of events within the overall crisis. The outturn could be very different, but logic suggests the following. Interest rates will rise until bank failures materialize. Meanwhile, financial assets will have fallen in value, possibly very quickly. Then we can expect monetary policy to expand to rescue the commercial banks, suppress bond yields and to finance soaring government deficits.