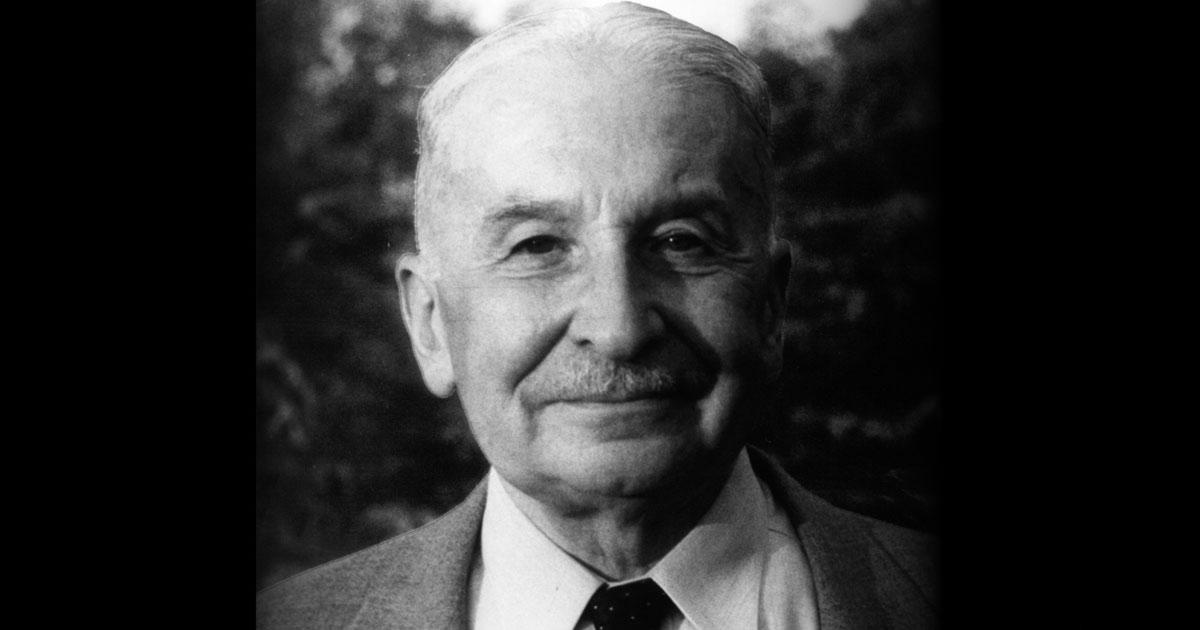

In a recent blog post on the Marginal Revolution blog, Ludwig von Mises is categorized as an underrated thinker. That’s undoubtedly true, especially when considering his many groundbreaking contributions to economics. Mises was also one of the first to be named a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association in 1969. His contributions to economic theory were many and significant and were largely recognized by his contemporaries. But while they are difficult to deny, Mises still gets very little recognition today.

Mises is frighteningly often dismissed as a “crank” or “ideologue” by present-day know-it-alls who are clearly ignorant of recent history of economic thought. The blog post at “MR,” which comments very briefly on Mises’s main works, is therefore an important reminder of Mises’s strong legacy. But it is also interesting because it provides insight into how a non-Austrian who is (or at least should be) well aware of Austrian economic theory sees Mises’s work.

The blog post is written by Tyler Cowen, a professor of economics at George Mason University who has recently gained online notoriety as a columnist, blogger, and podcast host. As a longtime colleague with Austrian economists, both faculty and graduate students, in the GMU economics department, many would assume Cowen to know much about this tradition and, especially, its main works.

Nevertheless, there is much to agree with Cowen on. He starts by pointing to Socialism and Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth as great contribution. He then moves on to state that he likes Liberalism and Bureaucracy. Cowen thereafter writes:

Human Action is big, cranky, and dogmatic, but for some people a useful tonic and alternative to the usual stuff. I can’t say I have ever really liked it, and in an odd way the whole emphasis on “Man acts” undoes at least one part of marginalism.

I admit that I do not quite understand how starting one’s analysis with human action “undoes … part of marginalism.” A more reasonable conclusion, at least from my perspective, is that this part of marginalism, whichever it may be, might be wrong or, at least, ill founded. But it would be easier to tell if Cowen had given us a clue what part he might be talking about.

The much larger problem is to call Mises’s systematic treatise “cranky” and “dogmatic.” I have the feeling that Cowen is referring to praxeology rather than Mises’s conclusions, even though the conclusions of course are stated without exceptions. That’s expected from theory that is derived logically from a true axiom: either the logic is wrong, or they are true. There is no reason to discussion “exceptions” because there are none.

But, as is common nowadays, many mistakenly believe that opening for exceptions and not being dogmatic is a sign of wisdom or scholarship. Likewise, they seem to think that taking a middle position is automatically “nuanced.” It can be, of course, but not by virtue of simply being in the middle. There is no middle ground between food and poison, as Ayn Rand would say. There is also, to borrow from Aristotle, no “golden middle” between truth and falsity, between right and wrong, or between ethical and unethical.

Praxeology is dogmatic in the same sense as truth is either true or it is not. It is not “nuanced” in the sense that empirical analyses are, because they always leave room for interpretation. It doesn’t matter how large a database or how sophisticated statistical methods—you cannot ever be certain that your findings are accurate. When people force praxeology into this frame, it appears dogmatic. But it is so for a reason: it must be.

Praxeology claims to establish the truth. This means that, from a scholarly perspective, praxeology should be considered the gold standard: it makes very strong claims, which can then be properly assessed and, if wrong, rejected. “Nuance” here means allowing for and including error. After all, praxeology is of the same kind as mathematics. But few would reject mathematics because it “dogmatically” holds that 2 + 2 = 4 instead of being more “nuanced” (allowing for 2 + 2 4 at least sometimes).

Cowen would know this if he understood praxeology, but there is no reason to assume that he does. His comment on Mises’s dogmatism suggests as much. So it appears reasonable to assume that he has the same type of shallow understanding of Austrian conclusions as his fellow non-Austrian GMU economics professor Bryan Caplan. The latter has written several essays on why he is not an Austrian, showing the world that he knows the terminology and conclusions but not the reasoning or rationale.

It is sad that Mises to this day is misunderstood. While Cowen indeed gives Mises well-deserved credit, doing so while dismissing his magnum opus as “dogmatic” and “cranky” is at best odd and bittersweet praise.