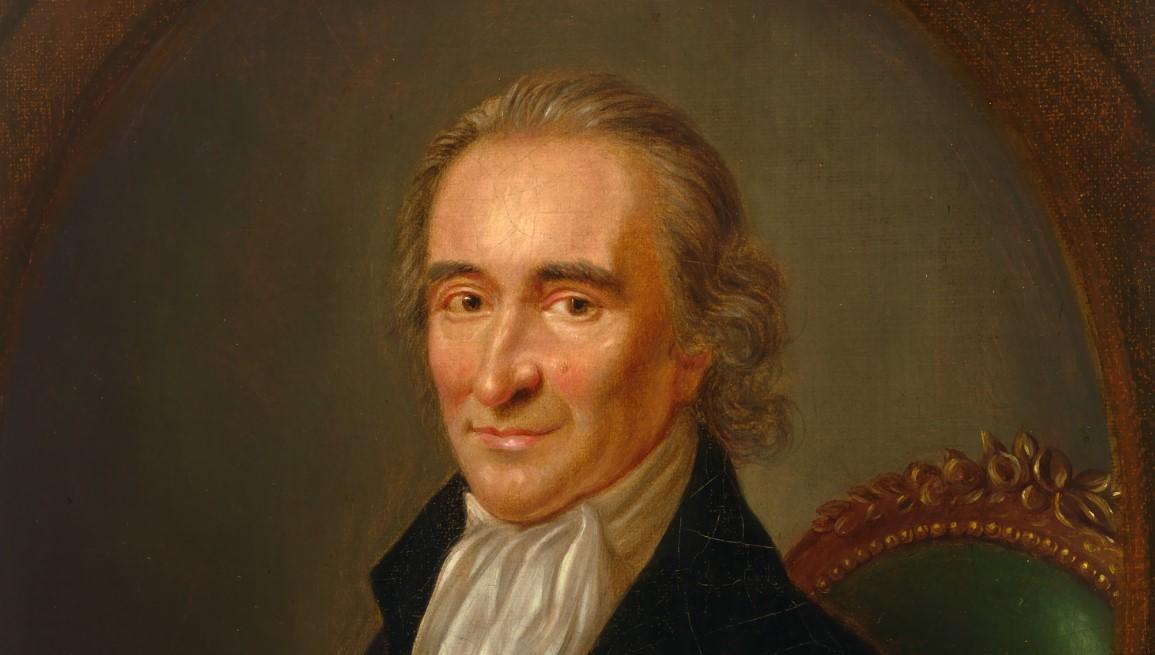

If Tom Cruise was Born on the Fourth of July, then he can thank Thomas Paine, who can be said to have been born on January 10, 1776, with the publication of his incendiary essay Common Sense. In this pamphlet, which he priced cheaply (at two shillings), Paine argued passionately for independence from England, and he wrote in a direct style that readers could understand.

Common Sense relieved the political constipation of the Second Continental Congress, which was stalled between reconciliation and independence. The seventy-seven-page pamphlet blasphemed the English king as a royal brute and obliterated the arguments opposing independence. Furthermore, it presented the issues in terms of utmost gravity: “The cause of America is, in a great measure, the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances have, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all lovers of mankind are affected.”

The stakes were high. Paine was calling on Americans to save the world, not only through arms but by repudiating their saintly icon, George III, who in truth was nothing but a “crowned ruffian,” as all monarchs were. John Locke had argued that states exist to protect man’s natural rights; Paine argued instead that they were born in “naked conquest and plunder.” Independence would also free America from Europe’s wars and quarrels, whereas the current colonial alliance would “set us at variance with nations . . . against whom we have neither anger nor complaint.”

Common Sense swept through all thirteen colonies and established strong support for secession—enough, at least, to kick Congress into action. John Adams, who hated Paine, later conceded that “without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.” Murray Rothbard concluded that “Paine had, at a single blow, become the voice of the American Revolution and the greatest single force in propelling it to completion and independence.”

“So gripping was Paine’s prose,” writes Jill Lepore in the New Yorker, “and so vast was its reach, that Adams once complained to Jefferson, ‘History is to ascribe the American Revolution to Thomas Paine.’” But of course, almost no one does. Paine is listed as one of the less significant founders, when he’s listed at all. When Benjamin Franklin died in 1790, some twenty thousand people attended his funeral. When Paine died in 1809, six people paid their respects, none of whom were dignitaries.

A mostly self-educated man, Paine went on to be the eighteenth century’s bestselling author, but also one of the most reviled. He mercilessly pummeled the government elites for their hypocrisy and abuses, as well as their disdain for commoners. As he wrote in a footnote to part one of Rights of Man (1791): “It is scarcely possible to touch on any subject, that will not suggest an allusion to some corruption in governments.”

In part two of Rights of Man (1792), Paine condemned English law and politics, for which he was tried in absentia for seditious libel while, ironically, arguing for sparing the life of Louis XVI in the French Assembly. During Paine’s trial, the crown’s prosecutor accused Paine of being a traitor and a drunken roisterer who had vilified Parliament and king. Among the evidence he cited was a letter Paine had written to the attorney general in which he stated that “the Government of England is [the greatest] perfection of fraud and corruption that ever took place since governments began.”

For four hours, Paine’s defense argued that he was innocent by virtue of freedom of the press. It carried no weight with the Crown’s handpicked jury—all wealthy, plump, and respectable men filled with icy hostility toward the defendant.

Paine’s Integrity

There are elements in Paine’s political writings that appeal to statists of varying degrees. Was he merely a pen for hire? For the most part, at least, I would say no. Yet even though Paine bashed government throughout his writings, he was one of the first to call for a stronger central government in 1783.

As I wrote in 2010, Paine’s “idea of strengthening the Articles of Confederation was to ‘add a Continental legislature to Congress, to be elected by the several States.’ When he was asked to propose his suggestion in a newspaper article, he declined, saying he ‘did not think the country was quite wrong enough to be put right.’”

His solidarity with liberty came in 1786 with his essay on paper money:

When an assembly undertakes to issue paper as money, the whole system of safety and certainty is overturned, and property set afloat. Paper notes given and taken between individuals as a promise of payment is one thing, but paper issued by an assembly as money is another thing. It is like putting an apparition in the place of a man; it vanishes with looking at it, and nothing remains but the air.

He went on to enumerate many more evils of paper money.

Paine has been dealt a cruel injustice. A case could be made that he is the country’s greatest founder by far: no Common Sense, no Declaration of Independence. Yet I’ve discovered that many Americans only vaguely recall mention of his name somewhere.