On April 23, 2003, in South Side Chicago, Reverend Jeremiah Wright cursed America for treating blacks as less than human.

Such harsh rhetoric should not seem surprising given the US government’s history of involvement in race relations. Judge Andrew P. Napolitano takes us through that history in his book Dred Scott’s Revenge: A Legal History of Race and Freedom in America.

Most readers have heard about black lynchings that gripped the South for generations following the War for Southern Independence. But how many know lynchings were often a major social event? “Witnesses often included the entire white community,” Napolitano tells us,

and, in many cases, the victim’s body was cut up and pieces were handed out as souvenirs. . . .

The local police, governments of each Southern state, and every American president from Ulysses S. Grant to Harry S. Truman allowed this to take place. . . .

Blacks were lynched for being economically successful, being more than minimally educated (they were “too uppity”), failing to step aside for a white man’s car, being politically active, staring whites in the eye, and even for protesting against lynchings. Many victims were innocent bystanders guilty of only being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The men and women who committed these crimes . . . were educated merchants, laborers, machine operators, teachers, physicians, lawyers, policemen, and students; they were family men and women who came to believe that keeping black people “in their place” involved nothing less than pest control.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Slavery and its proliferation were two of the most contentious issues in early nineteenth-century America. Abolitionists claimed that any slave taken to a free state was thereby freed. But slaves were regarded as the property of their masters, and one’s property cannot legally be forfeited by crossing a state line.

Dred Scott and his wife, seeking the status of citizens, “had to show that they had become free while in Illinois or the Wisconsin territory and that they remained free when they were brought back to Missouri,” a slave state. In 1852 the Missouri Supreme Court ruled against Scott, who then appealed to the US Supreme Court in 1857.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney “did not always rule against slaves,” Napolitano tells us. For instance:

In the Amistad case, the Court freed a group of Africans in 1841 who were seized as slaves and rebelled aboard a slave trip. Because the slave trade had been constitutionally outlawed in 1808 pursuant to the Importation Clause, the Court found that the Africans had been illegally seized and their status as slaves could not be justified by the plain text of the Constitution.

In Dred Scott, two of the nine justices wrote opinions that sided with Scott. Writing in the majority, however, Chief Justice Taney, a former slaveholder, claimed that blacks were not citizens and were therefore not entitled to the rights and privileges accorded to citizens. The court later ruled that the Reconstruction Amendments superseded Taney’s ruling, but the damage had been done. Blacks had been stamped as second-class citizens.

Taney’s decision, Napolitano concludes, was “government-endorsed racism.”

Lincoln and Reconstruction

Abraham Lincoln came into office, and the South seceded; he told them they had no right to leave and tricked them into firing the first shot. Four years and a million casualties later, the South surrendered. As a voluntary association of free states, the Union was dead. The South lay in ruins, and the slaves, by virtue of the Thirteenth Amendment ratified on December 18, 1865, were no longer slaves. But were they free?

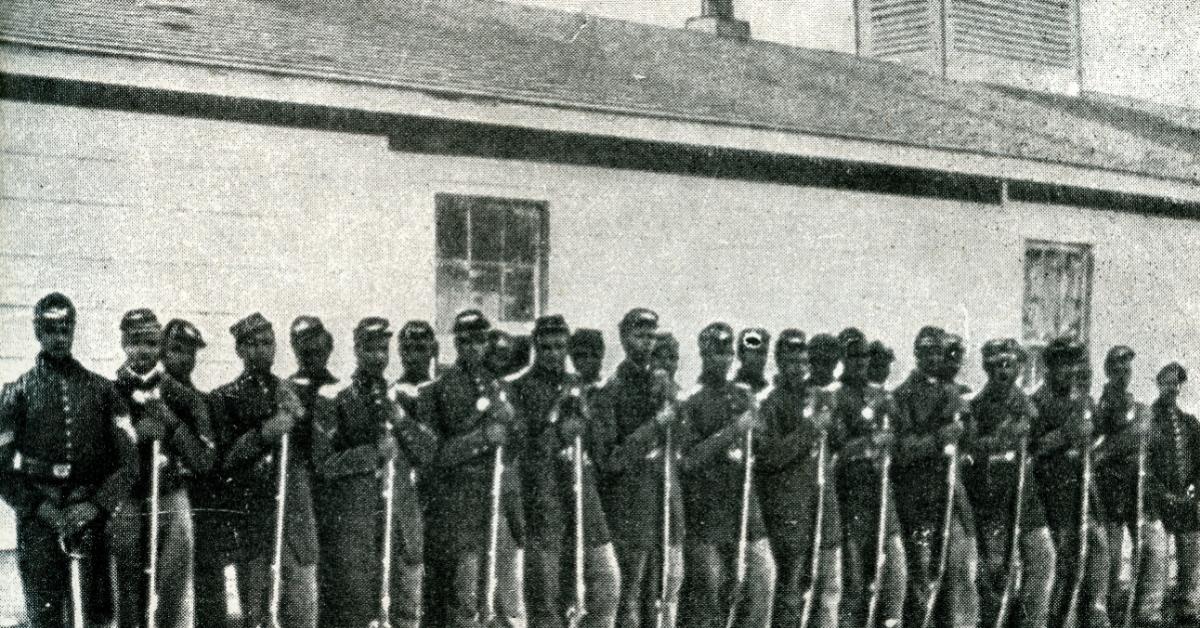

The Reconstruction era (1865–77) was, among other things, an attempt to elevate blacks to full citizenship.

Following a year of violent attacks against Blacks in the South, in 1866 Congress federalized the protection of civil rights, and placed formerly secessionist states under the control of the U.S. military, requiring ex-Confederate states to adopt guarantees for the civil rights of freedmen before they could be readmitted to the Union.

President Andrew Johnson pursued a lenient Reconstruction policy that angered radical Republicans. Congress overrode Johnson’s veto twice in 1867 to pass bills prolonging military occupation of the South in every state except Tennessee, Johnson’s home state. The goal was to create loyal governments.

The acts were about power, not freedom or equality. Congress passed another bill authorizing anyone but former Confederates to write the new state constitutions. In other words, only blacks, carpetbaggers, and scalawags were qualified. White Southerners seethed with resentment.

Organizations of white militants began to flourish, especially when Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1869. Groups such as the White League, the Red Shirts, and the Ku Klux Klan used violence and intimidation to keep blacks from holding political office or voting for anyone supporting Reconstruction.

By 1877, all federal troops had left the South. Reconstruction had been a failure. Republicans could not force the South to bow to their decrees. On the contrary, their orders inflamed passions against the Union and especially against blacks.

To white Southerners, blacks came to personify federal intervention.

Jim Crow

The period known as Jim Crow ran from the 1890s to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. During this period, “Southern states began to reinforce, in law and state constitutional provisions, the subordinate position of blacks in society.” Jim Crow “became shorthand for the continued lawful degradation of blacks.”

Racial ostracism extended to every place where the two races might come together, even cemeteries. “As witnesses in court, blacks and whites had to swear on different Bibles.” Factory workers in Alabama had to look out different windows than whites. By 1910, legalized segregation had taken hold in every state of the South.

Among the reasons for the extreme racism, Napolitano cites the terrible violence of the war, the Union’s wanton destruction of private property in the South, Sherman’s “scorched earth” policy, and the military occupation during Reconstruction, in which the rule of law was abandoned.

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), eight of nine Supreme Court justices refused to rule against Jim Crow. Plessy was “used to defend Jim Crow laws from judicial scrutiny until the second half of the twentieth century.” The majority reasoned that separate but equal accommodations did not violate the Constitution because both races were treated equally under the law.

Roughly seven million black people quit the South between 1900 and 1970, even though in doing so they faced unfriendly conditions up North. It was government that perpetuated the endless years of discrimination, Napolitano claims. It afforded “no relief or justice for persecuted blacks.”

He goes on to tell us about the plight of blacks in the World Wars, the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment, Brown v. Board of Education, oppressive aspects of the civil rights legislation, the ’60s riots, Barry Goldwater, and Jackie Robinson—Major League Baseball’s first black player.

In 1947 Jackie Robinson turned out to be both the best player and the best person to endure the threats and harassment of playing in the majors:

By having nothing to do with his triumph, the government, albeit unknowingly, let Jack Roosevelt Robinson become a black hero with whom whites could identify. Without such a hero, white Americans may have never cared enough about black Americans to be bothered by racial injustice. Jackie Robinson did for his country what its federal government could not: he renewed the civil rights revolution. (emphasis added)

Judge Napolitano’s book is an engaging, informative read about race relations and government, subjects we need to know as much as possible if we are to avoid repeating the mistake of government-enforced racism in today’s America.