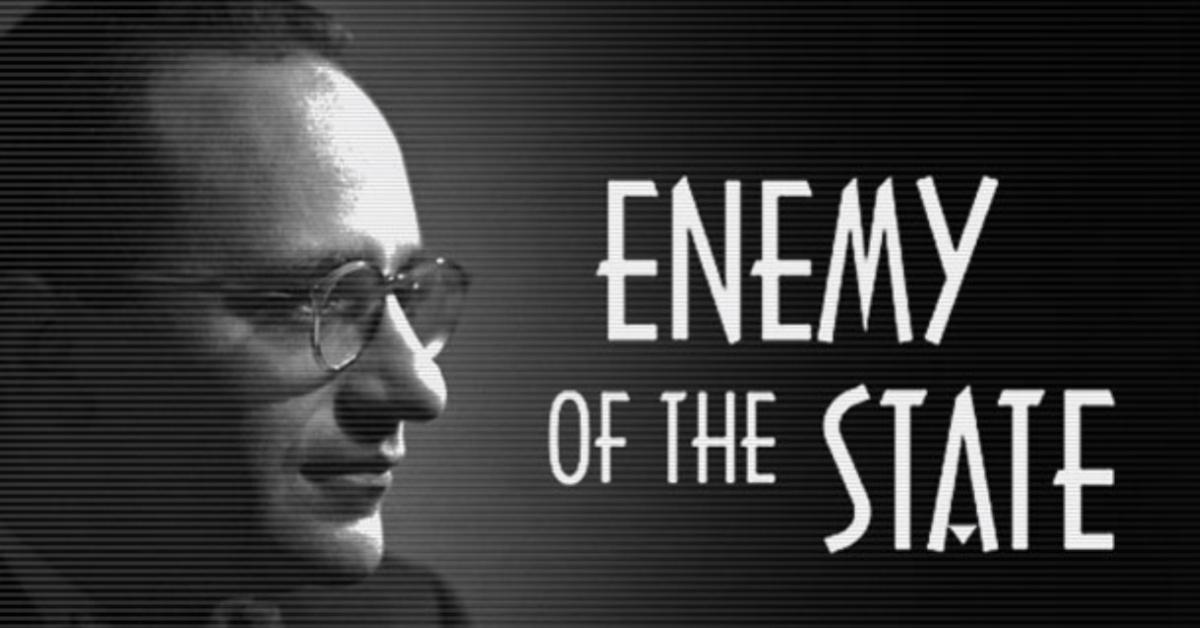

Murray Newton Rothbard, perhaps the greatest enemy of the state in the second half of the twentieth century, would have recently celebrated his ninety-seventh birthday had he lived.

Men are not salmon, those unique creatures that swim against the current. Most people “go with the flow” and allow the pace of events to dictate their lives, at least in that few consciously choose to reject the current order of things, declare it to be profoundly wrong, and act on it. Rothbard was one of those few.

The State qua State

Rothbard’s greatest practical achievement was the demystification of the state: an entity that must be cloaked in apologias and ringed with armed men in order to survive. Before his classic piece, The Anatomy of the State, there was a serious lull in substantive writing on the state qua state, the actual substance of what a state is, and what it necessarily implies.

All the justifications for the state conjured up by the hired guns of academia in league with it serve to camouflage the actual operation of the entity itself. Since there is no “it” to the state, meaning it has no separate consciousness, it is nothing but a shorthand for the individuals who make it up. The only difference between the people who make up the state and the plebians outside it is political power, which is, as per Franz Oppenheimer, the ability to satisfy one’s material needs by the means of coercion.

Since the state is not its own entity, there cannot be special ethics that apply only to it and not to the individual (deeper yet, how can there be special ethics at all?).

Ergo, the state is a shorthand for the political-power-using individuals who make it up, who also by necessity operate under the same ethics as any non-bureaucrat does. Since the state is involved in taxation, conscription, regulation of business, warfare, welfare, censorship, and imprisonment among other things, it follows that the state is a criminal organization of the highest caliber. No brutal mafioso or cruel feudal baron could come within screaming distance of the criminality of the state, and this was Rothbard’s chief insight.

Little wonder why the intellectual bodyguard of the state, academia, was not overly fond of him.

The Victory of the Radicals

Armed with his mentor, Ludwig von Mises’s, insight that socialism cannot long persist due to the impossibility of economic calculation and the death of revolutionary enthusiasm, Rothbard saw the cracks in the Soviet edifice long before his contemporaries. His biographer, Justin Raimondo, quotes him as follows:

I am not expert enough to say [how] far this progress has already gone in the Soviet Union. But the point is that it must, in the nature of things, be underway already, and its importance will grow as time goes on. If we realize this, and remember also that revolutionary inspiration has always, historically, died out after a time, we will see that time is on our side, and we will realize that we need not dig in for a long and bloody battle to the death with an enemy that is even now withering from within.

Though the victory was far from total, Rothbard and his like were vindicated when the Soviet Union and its worm-eaten client states collapsed under the weight of their own bureaucracies, much as he predicted. After the death of Chairman Mao, China gave up the goal of building communism and acquiesced to gradual economic liberalization. The West reaped the fruits of its own liberalization after seeing the error of the postwar Keynesian consensus.

If Rothbard and the underground liberty movement around the world have a political legacy that one can see in the daily papers, it is the rout of outright socialism.

Liberty since Rothbard

Sadly, the gains the economist oversaw in his last years have not been well stewarded, let alone advanced.

Freedom House measures the trends of civil liberties over time. Since 2006, there has been an ominous one: every year, more countries lose liberty than gain it. By their estimates, as of 2021, only one in five people live in free countries.

Freedom House’s definition of liberty is relative, not absolute. As a result, they habitually turn a blind eye to the depredations of supposedly free Western states. Rothbard would hardly call a state with a progressive income tax, eminent domain, gun control, conscription, a prison industrial complex, and a standing army a free one.

The Great Recession, which blindsided mainstream Washington yet was entirely foreseeable from the Rothbardian angle, further brought banking under the control of the state and served as a launchpad for the Barack Obama spending bonanza. Since Donald Trump had a dubious commitment to market rights, it should not have been surprising that he spent even faster than his predecessor, and President Joe Biden proceeded to spend more than Trump.

To really see where the world went wrong after Rothbard’s time, one has to put state spending and related metrics aside to focus on other things—things that would not have been conceivable in his time.

Coronavirus, and more specifically how the state responded to it, tells the biggest story of all. China locked down billions of people. Australia built gulags. The United Kingdom arrested people for being outside their homes. Slovenia banned the unvaccinated from buying gasoline. New Zealand shut itself off from the rest of the world. The European Union made vaccine passports.

Oppression overseas is one thing, and for a man who saw the horrors of the twentieth century, it would not have surprised him. The same oppression at home is another ballgame. American churches were closed, many never to reopen. American businesses were closed, many also never to reopen. Masks were mandated first, and then so was the vaccine, with at one point over 100 million Americans subject to the mandates. Americans were spied on to new degrees by their own government. Coronavirus brought oppression to American soil in a way that has hardly been felt before in living memory.

If only Rothbard and his typewriter were still here to shred these absurdities with editorials.

The Happy Warrior

These setbacks for liberty are real, but the core of the Rothbardian outlook was never settling and always persevering, which is why he penned For a New Liberty, his detailed plans for an anarcho-capitalist society.

In contrast to other political outsiders, who can often be called a grim lot, Rothbard was a joyous fellow and called himself a happy warrior. He lived his life and fought his battles with an upbeat demeanor that the liberty movement must recall and emulate, especially after the hard defeats of the last few years. Putting aside for a moment all his insights, the veritable library he wrote, and the principles he elucidated, one thing the liberty movement must take from his legacy is to be as he was: happy warriors.

Happy belated birthday, Murray Rothbard, and may there be more like you soon.