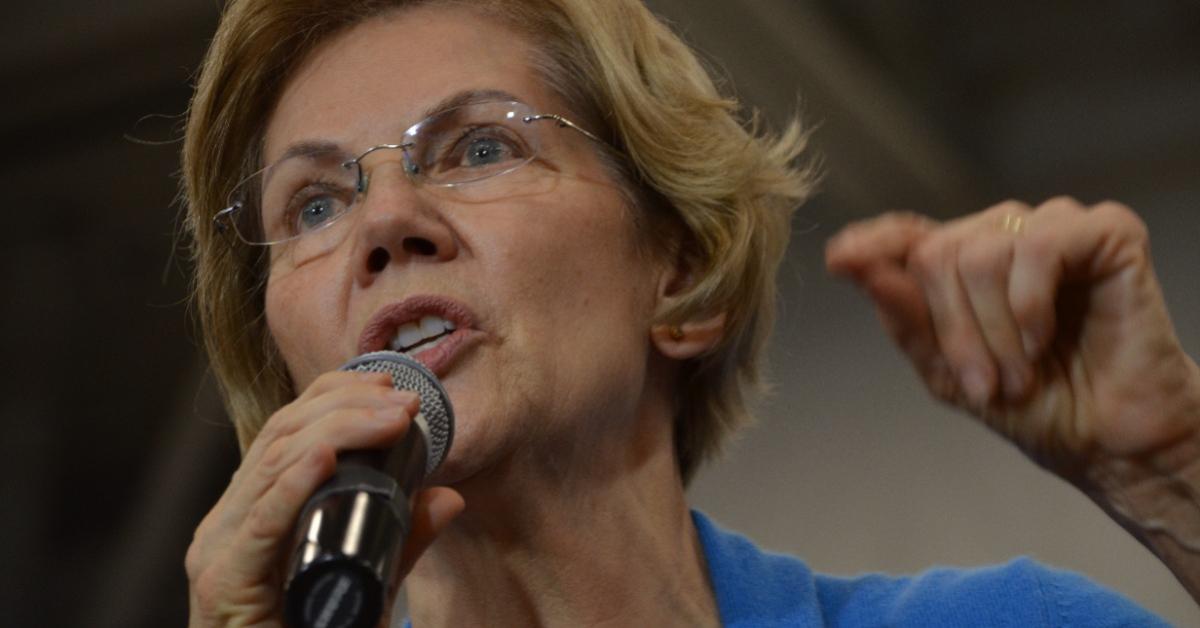

As the financial ripples following the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) continue to run through the financial sector, a predictable voice has weighed in on the affair, and, as always, giving bad advice. Elizabeth Warren, never one to skip a chance to publicly gnaw on a financial carcass, writes in the New York Times that the entire problem is lack of government regulation. Of course.

The US senator from Massachusetts has spent most of her Washington career calling for both easy money and a financial sector that will “serve the little guy” and be the paragon of fiscal responsibility at the same time. Her demands are mutually exclusive, but that doesn’t stop her from trying to be the voice of financial reason from the left. She writes in the Times:

No one should be mistaken about what unfolded over the past few days in the U.S. banking system: These recent bank failures are the direct result of leaders in Washington weakening the financial rules.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act to protect consumers and ensure that big banks could never again take down the economy and destroy millions of lives. Wall Street chief executives and their armies of lawyers and lobbyists hated this law. They spent millions trying to defeat it, and, when they lost, spent millions more trying to weaken it.

Since none of the changes to Dodd-Frank in 2018 would have prevented the collapse of SVB, Warren is attempting to apply a general concern (easing of some bank regulations) to a specific event. But by claiming that financial crises are the result of lax regulation, Warren overlooks the real reason that we had the 2008 meltdown and that the financial system is also in near crisis today: easy money from the Federal Reserve System.

To put it mildly, Elizabeth Warren lives in an economic netherworld in which easy money equals responsible monetary management. Banks give near-unlimited credit to people with zero or poor credit histories to buy homes or cars, the Fed stays in permanent money-pumping mode, lending is directed by the political system, and all the while banks are regulated by a green-eyeshade regime that makes Ebenezer Scrooge look like Wilkins Micawber. Perhaps a typical progressive Massachusetts voter might be able to logically tie these things together, but for people grounded in causal realism, her comments make no sense.

Peter Schiff noted in his famous speech at the Mises Institute in 2009 that a financial system should be regulated by profits and losses. However, that kind of system cannot have government bailouts, easy money triggered by central banks, or political favoritism, as government interference will overpower natural market regulation because the political system will declare winners and losers.

The system that Warren and others like Paul Krugman demand is something close to the regulated banking cartel that was in place from the New Deal to about 1980. Writes Krugman:

The banking industry that emerged from that collapse was tightly regulated, far less colorful than it had been before the Depression, and far less lucrative for those who ran it. Banking became boring, partly because bankers were so conservative about lending: Household debt, which had fallen sharply as a percentage of G.D.P. during the Depression and World War II, stayed far below pre-1930s levels.

He adds: “Strange to say, this era of boring banking was also an era of spectacular economic progress for most Americans.”

Far from being a time of “spectacular economic progress,” the late 1970s was a period of stagflation. Inflation rates hit double digits and unemployment was not far behind. During the so-called golden era of which Krugman writes, Regulation Q, which was created by the Federal Reserve Board in 1933, restricted interest rates on time deposits. This and other regulations greatly restricted bank lending to ensure that only the best customers received loans. This regime bumped along with no major bank failures or major problems until the late 1970s.

When the Carter administration sought to loosen lending rules and abolish Regulation Q, it wasn’t out of ideology but rather because American banks were facing a disintermediation crisis. For that matter, even President Ronald Reagan’s so-called signature financial deregulation measure, the 1982 Garn-St. Germain Act, was much more the initiative of Ferdinand St. Germain, the Democratic chairman of the House Banking Committee, than anything from the White House.

All of this contradicts the standard narrative we hear regularly from Krugman and progressives like Warren, but the history of financial and economic deregulation over the past forty-five years has had very little to do with ideology and more to do with trying to mitigate the growing problems caused by the regulatory regimes themselves, something I pointed out in a reevaluation of the Carter presidency.

With the appointment of Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1987, the Fed launched an easy-money regime that has lasted nearly forty years, and (contra Warren) easy money means consequences. By pushing interest rates to near zero, the Fed has eliminated the attractiveness of interest-bearing securities as investments, driving banks and other financial institutions to other financial instruments. One of the reasons that so many investment banks have been holding mortgage-backed securities is because these instruments have had better returns than instruments paying interest.

This brings us to the great contradiction: progressives like Warren have demanded that the Fed suppress interest rates, all the while denouncing the hard fact that artificially low interest rates drive investors—including banks—to embrace riskier lending and outside investment.

Neither has Warren limited her contradictory demands to banking and finance. She loudly advocates for rent controls—all the while decrying housing shortages (which rent controls would make even worse)—and, for good measure, demands government-enforced price controls for the rest of the economy. She also is a leading voice for student loan forgiveness, conveniently overlooking the fact that such “forgiveness” measures only transfer responsibility from borrowers to other taxpayers and hardly fits her ideal of regulated lending.

Second, Silicon Valley and the financial industry tied to it have been cash cows for Democratic Party candidates for the past several election cycles. Even leaving out Samuel Bankman-Fried and the millions laundered mostly to Democrats through the now-collapsed FTX exchange, no regulator tied to a Democratic regime is going to do anything to shut off the political money spigot that has given the party a huge edge the past two elections.

The symbiotic relationship between Washington and the tech industry is simply not conducive to the kind of financial oversight Warren demands, something she almost surely understands. That the feds are bailing out everyone associated with SVB, even above the $250,000 limit for federal deposit insurance, probably is as much a political payoff as it is a measure to keep the markets from being further frightened.

Warren, the New York Times, and the assortment of progressive pundits are spinning this crisis—and nearly every other financial one—as a regulatory problem that can be solved by all-knowing financial clairvoyance. But none of them are calling for an end to the real problem: the easy-money regime that is rotting out the economy and especially the financial sector from the inside out.