Of the many steps taken to combat the depression during the Roosevelt administration’s famous first hundred days, none was more significant than the passage of the June 16, 1933 Banking Act providing for the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

No step was more significant, and none has been more misunderstood. To delve into that misunderstanding is to realize, among other things, just how hard it can be to answer the question, “how much credit does the New Deal deserve for ending the Great Depression?”

Deposit Insurance Myths

The Banking Act of 1933 was the most sweeping reform of the United States banking system since the passage of the Federal Reserve Act. Also known as the Glass-Steagall Act, after its Democratic co-sponsors Virginia Senator Carter Glass and Alabama Congressman Henry Steagall, it subjected commercial banks to three new sorts of regulation: it prohibited them from underwriting or otherwise dealing in corporate securities; it imposed limits on the interest rates they could pay on deposits; and it established the FDIC, compelling all Federal Reserve member banks to take part in its deposit insurance scheme, and giving non-member state banks the option of doing so, on the condition (which was later modified to apply to large state banks only) that they also become Fed members. While all three reforms had important consequences, either at once or in the long run, deposit insurance had the most obvious bearing on the course of economic recovery, and it’s with that reform alone that this essay is concerned.

Because banks needed time both to qualify for insurance and to contribute to the FDIC’s funding by purchasing shares in it, the FDIC’s opening was scheduled for January 1, 1934, when it would start insuring deposits. Under a temporary plan, all deposits would be insured up to $2500. That plan was supposed to give way to a permanent one, with much higher coverage limits, on July 1, 1934. But in mid-June, Congress decided to put off the permanent plan until July 1, 1935, while raising the temporary plan’s coverage to $5000 for all accounts. The start of the permanent plan was postponed once more, until August 31, 1935, by a Congressional resolution. Finally, just days before that deadline, the 1935 Banking Act put a new permanent plan, preserving the $5000 coverage limit, into effect. In the meantime, the National Housing Act, passed on June 17, 1934, provided for the establishment of a Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), to guarantee deposits at savings and loans much as the FDIC guaranteed those kept at banks.

So much for the settled facts. The misunderstandings have mainly to do with the novelty of the deposit insurance plan, the purpose it was meant to serve, and the part that the Roosevelt Administration played in its adoption. In 1960, Carter Golembe (1960), a highly regarded bank consultant then working at the FDIC, tried to set the record straight. “Deposit insurance,” Golembe wrote, “was not a novel idea; protection of the small depositor, while important, was not its primary purpose; and, finally, it was the only important piece of legislation during the New Deal’s famous ‘one hundred days’ which was neither requested nor supported by the new administration.”[1]

Relief or Recovery?

Golembe’s second point justifies treating deposit insurance as having made an important contribution to the process of economic recovery. Instead of merely being aimed at protecting depositors, as many suppose, the more crucial purpose of insurance was, Golembe says, to “restore to the community, as quickly as possible, circulating medium destroyed or made unavailable as a consequence of bank failures” (ibid., 189). Insurance was, in other words, an element of monetary or, if one prefers, macroeconomic, policy rather than one of mere redistribution, with the correspondingly more ambitious goals of getting people to put their paper money back into the banks, ruling-out further bank runs, and reviving bank lending.

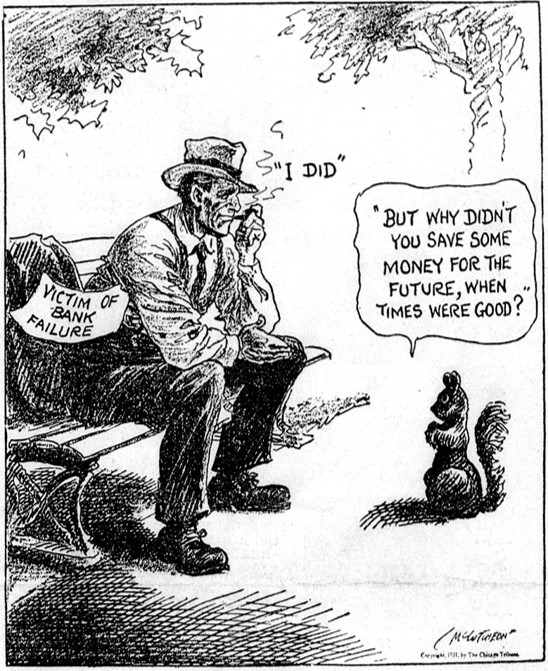

To appreciate the need for some such reform, one need only realize that the banking system that emerged from the national bank holiday was essentially the same one that led to it. Of course many closed banks would never be licensed to reopen. But thousands would be, including many rural banks of the sort that accounted for most of the pre-holiday failures. In the short run, the Fed’s agreement to cover all cash withdrawals from such banks, together with Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) capital injections, would help bolster confidence in the reopened banks. But those measures were mere stopgaps that could neither rule out future runs nor convince people to redeposit all the paper currency they’d hoarded. If confidence in banks was to be fully restored, and prevented from ever melting away again, something more had to be done.

In defending his insurance plan on May 19th, 1933, Steagall made the macroeconomic case for it clear. The public, he said, was still

afraid to deposit their money in the banks, and the banks are afraid to employ their deposits in the extension of bank credit for the support of trade and commerce. Businessmen and investors are victimized by the same fear. The result is curtailment of business, decline in values, idleness, unemployment, breadlines, national depression, and distress. We must resume the use of bank credit if we are to find our way out of our present difficulties.

In fact, had deposit insurance not served a macroeconomic purpose, Congress would almost certainly have spurned Steagall’s plan, just as it spurned scores of similar plans introduced to it over the course of the previous four decades. And it would have done so for perfectly good reasons.

History Lessons

The FDIC wasn’t the world’s first national-level deposit insurance arrangement—Czechoslovakia beat the United States to that punch by a decade. Nor was it the United States’s first experiment with such insurance. Various state governments tried guaranteeing both banknotes and bank deposits. The first to do so was New York, which established a bank “Safety-Fund” in 1829. The permanent FDIC plan shared many features with the Safety Fund, including (ultimately) the latter’s provision exempting the owners of banks that contributed to the fund from double liability—a then-common arrangement that required shareholders of a failed bank to fork up as much as their shares’ par value if that proved necessary to make the bank’s creditors whole.[2]

Begun with high hopes, the Safety Fund ended up a fiasco: by the early 1840s, it was broke, so the government had to lend it the money with which it continued to meet its outstanding commitments. What Howard Bodenhorn (2002, 157, 182) refers to as a “combustible” mixture of inadequate supervision (including ineffectual or nonexistent portfolio restrictions), “mispriced insurance premia, a limited ability to impose emergency assessments, and fraud” caused the fund to quickly fall victim to “the standard insurance problems of moral hazard and adverse selection.”[3]

The Safety Fund’s undoing came too late to stop Vermont and Michigan from setting up similar systems, with similar results. Michigan’s fund, established in 1836, went bust just five years later, having failed to pay a nickel to any of the creditors it was supposed to insure (Golembe 1960, 185). Vermont’s version, set up in 1831, survived longer, but ultimately went awry by letting its members quit whenever they pleased! By 1859, none was left, so it could only cover 72 percent of its obligations, leaving Vermont taxpayers holding the bag for the rest (Golembe and Warburton 1958, 108).

Three other antebellum insurance schemes—in Indiana, Ohio, and Iowa—did much better. But unlike the New York, Vermont, and Michigan arrangements—and also unlike the FDIC’s plan— they depended on the unlimited mutual liability of their members. Mutual liability gave participating banks a powerful incentive to police one another and to close down suspect banks before they became deeply insolvent. All three systems had good records, and all were still solvent when a federal tax on state banknotes, aimed at compelling state banks to join the then-new national banking system, shut them down (Calomiris 1990, 288; Selgin 2000).

Because the tax on state banknotes nearly did away with state banks altogether, for a while it looked as though the United States had seen the last of its experiments with state-sponsored deposit insurance. But over time, as checks came to be more widely used in payments, non-note-issuing banks became increasingly viable; and it was not long before hundreds were being chartered every year. The outcome of this was the “dual” banking system, consisting of a mix of banks with federal (“national”) and state charters, that survives to this day.

Until several decades ago, most United States banks, whether state or national, were “unit” banks, with a single office only, and correspondingly heavy exposure to local shocks. Because state banks tended to be smaller than national banks, they were especially vulnerable. Not surprisingly, such banks failed relatively often, putting pressure on their sponsoring governments to come up with ways to protect their creditors. So it happened that what first looked like state deposit insurance schemes’ last curtain call turned out to be a mere intermission between two acts, with eight new schemes coming on stage between 1917 and 1927.

Alas, these later schemes merely “repeated and compounded the earlier errors of New York, Vermont, and Michigan” (Calomiris 1990, 288), and so ended up faring no better. Thanks mainly to the agricultural bust of the 1920s, by the spring of 1930 every one of them had gone belly-up.

Insurance vs. Branches

Those early twentieth-century deposit insurance schemes were all established in states—Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Texas, Mississippi, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Washington—where there was strong opposition to branch banking; where laws either prohibited branching altogether or put very strict limits on its growth; and where “business prosperity in general depended on one or two commodities” (White 1983, 191).[4] That was no coincidence. Not letting prospective bank depositors choose between unit and branch banks was one way to keep poorly-diversified unit banks in business. But it still left them exposed to runs once they got into hot water.

That’s where insurance came in. Here again, Carter Golembe (1960, 195) zeroes in on the truth. “[I]t is not reading too much into history,” Golembe says, to regard deposit insurance schemes as “attempts to maintain a banking system composed of thousands of independent banks by alleviating one serious shortcoming of such a system: its proneness to bank suspensions, in good times and bad.” Henry Steagall, who was second to none in his determination to save the United States’s small unit banks, made no bones about this. “This bill,” he said, referring to his May 1933 effort, “will preserve independent dual banking in the United States. … This is what the bill is intended to do” (ibid., 198).

Insurance and branching were, in short, rival reform options: one sought to preserve the unit banking status quo, and particularly state-chartered unit banks, despite their inherent weaknesses; the other would instead have allowed banks to branch statewide, if not nationwide, which would have meant more relatively large and well-diversified banks with branches, and many fewer smaller unit banks. Steagall favored the insurance option, while opposing branch banking tooth-and-nail. Carter Glass, his Senate Banking Committee counterpart, took the opposite position.

Until the Great Depression began, despite scores of attempts on behalf of each, neither federal deposit insurance nor branch banking seemed capable of gaining political traction. But as the Great Depression took its toll, and the number of bank failures mounted, so did the pressure to do something to stop runs, limit bank depositors’ losses, and otherwise overhaul the United States banking system. That pressure, plus some expert logrolling, finally broke the impasse. But it did so only after one of the more determined opponents of deposit insurance blinked.

That determined opponent was none other than Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Outliving a Cat

“In June 1933,” then Council of Economic Advisers Chair Christina Romer testified in 2009, “President Roosevelt worked with Congress to establish the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.” The occasion was a hearing on “Lessons from the Great Depression” being conducted by the Subcommittee on Economic Policy of the Senate Banking Committee.

Of course it’s true that Roosevelt helped establish the FDIC, in so far as it was his signature that turned the Glass-Steagall bill into a law. Yet Romer’s testimony is more than a little misleading: what she doesn’t say is that Roosevelt opposed the Glass-Steagall bill’s deposit insurance provision until the eleventh hour, even threatening to torpedo the whole bill unless it was taken out.

FDRs opposition to deposit insurance was sincere, earnest, and perfectly conventional. In October 1932, while campaigning for the presidency, he responded, privately, to a letter from a supporter urging him to publicly declare his support for federal deposit insurance as doing so would reassure the public while gaining him votes. Roosevelt demurred. Though it might be popular, he said, insurance was also “dangerous,” for in time it “would lead to laxity in bank management and carelessness on the part of both banker and depositor,” one result of which would be “an impossible drain on the Treasury” (Gates 2017, 310).

Once he was in office, Roosevelt’s opposition to deposit insurance became what one of his biographers calls his “major quarrel” with Congress on banking legislation (Freidel 1973, 441-2). Asked his opinion of deposit insurance during his very first press conference, on March 8th, Roosevelt repeated, off the record, the argument he’d made privately in his letter of the previous October. He added a rather nice numerical example of what he had in mind, and concluded by saying that he opposed “having the United States government liable for the mistakes and errors of individual banks and not [sic] putting a premium on unsound banking.” When a reporter pressed further, Roosevelt replied emphatically:

Q: You do have in mind guaranteeing deposits of banks on the new basis?

FDR: No; no government guarantee.

Q: You would have to have that guarantee under the new banking system.

FDR: There would have to be a guarantee? Oh, no. The government isn’t going to guarantee any banks.

In fact, Roosevelt was not being entirely candid, for as we saw in a previous installment, by various provisions of the 1933 Emergency Banking Act the government and the Federal Reserve were in effect planning to guarantee the deposits of reopened banks for a time (Silber 2009). Roosevelt apparently saw no inconsistency between his acceptance of those emergency provisions and his opposition to more explicit and permanent deposit insurance. In any event, the emergency provisions, being stopgaps only, did not end the legislative battle for fundamental reform of the banking system that raged through 99 of the Roosevelt Administration’s first 100 days.

By mid-May, however, the tide of that battle was turning decidedly in favor of insurance. A new Steagall bill had made it to the Senate Committee, and Carter Glass, who had already gone so far as to include an optional deposit-insurance plan in his own bill, was persuaded to amend it further, to provide for temporary but mandatory and immediate insurance of all Fed member bank deposits. Arthur Vandenberg, who did that persuading, rose in the Senate to explain why he’d done so. “There is no remote possibility,” he said, “of adequate and competent economic recooperation [sic] in the United States in the next twelve months . . . until confidence in normal banking is restored; and in the face of the existing circumstances I am perfectly sure that the insurance of bank deposits immediately is the paramount and fundamental necessity of the moment.” Glass accepted Vandenberg’s suggested amendment, on the understanding that Steagall would in turn support his plan for separating investment and commercial banking. The amendment passed handily, allowing Glass’s bill to join Steagall’s in conference.

When Roosevelt learned what had happened, he was anything but pleased. Instead, on June 1st he called both Glass and Steagall to a meeting at the White House whose other attendees were a motley assortment of Administration critics of deposit insurance (Gates 2017, 316). He also wrote both Glass and Steagall individually, and the conference committee, threatening to veto any compromise that included deposit insurance. But knowing that the whole measure would fail without that provision, they all called the president’s bluff. At last he resigned himself to endorsing the reconciled bill’s insurance provisions, taking comfort in the temporary plan’s limited coverage, and joking with reporters afterwards that the bill had enjoyed “more lives than a cat.”

Role Reversal

How is it that Roosevelt so often gets credit for deposit insurance, despite having opposed it so relentlessly? One part of the explanation is that, once he’d signed off on it, Roosevelt himself took credit for it. His doing so merely amused his professional contemporaries, but it has confused later generations who have taken his self-praise at face value. Another is that Roosevelt’s criticisms of deposit insurance were often made either privately or off the record, while his efforts to kill it in Congress all took place behind closed doors. Finally, Roosevelt did sign the Glass-Steagall Act after all, instead of vetoing it as he’d threatened to do, so he at least deserves credit for that. Otherwise—if, say, Congress had instead had to override Roosevelt’s veto—deposit insurance would only qualify as a New Deal measure on strictly chronological grounds.

If the popular view of FDR as a champion of deposit insurance is more fiction than fact, the equally common view that Hoover opposed insurance isn’t much better. It’s true that, for most of his career, Hoover’s views on deposit insurance, and on banking reform more generally, differed little from Roosevelt’s, just as Roosevelt suggested in his March 8th press conference. Instead of favoring insurance, both men preferred Carter Glass’s original reform program. Thus on December 8th, 1931, Hoover (1951, 122) asked Congress to look into “the need for separation between the different kinds of banking; an enlargement of branch banking…; and the methods by which enlarged membership in the Federal Reserve System may be brought on,” without mentioning insurance, which he, like Roosevelt and Glass, still considered a bad idea.

But while Roosevelt continued to oppose insurance months after the February-March banking crisis, as that debacle worsened, it caused Hoover to change his mind. On February 28, 1933, he wrote the Federal Reserve Board, asking whether it considered it desirable

1) To establish some form of Federal guarantee of banking deposits; or

2) To establish clearing house systems in the affected areas; or

3) To allow the situation to drift along under the sporadic State and community solutions now in progress (Myers and Newton 1936, 359).

Despite his undeserved reputation as a “do nothing” President, Hoover certainly considered the third option unacceptable, including it only to compel the Board to choose between the others. On March 2nd, with the banking system in free fall, the Board replied that it wasn’t prepared to recommend deposit insurance, given the history of States’ experiments with it, and its “inherent dangers” (ibid., 362). To this Hoover at once replied as follows:

I am familiar with the inherent dangers in any form of federal guarantee of banking deposits, but I am wondering whether or not the situation has reached the time when the Board should give further consideration to this possibility (ibid., 364).

Hoover even included a “rough outline” of an insurance plan, asking the Board for its advice. But the Board replied that it preferred a nationwide bank holiday to any sort of guarantee. Two days later, Hoover handed the reins to FDR; who announced the bank holiday a day later.

FDR’s Last Laugh

If Roosevelt has gotten too much credit for the FDIC’s establishment, he deserves more credit than he’s received for having recognized the dangers it and similar deposit schemes pose, and for having preferred other options for that reason.

That deposit insurance wasn’t the only way to keep a banking system from collapsing was evident enough in 1933 from other countries’ experiences. Hoover (1951, 24), for one, had no trouble recognizing it:

That it was possible, by proper organization and inspection, to have a banking system in which depositors were safe was demonstrated by Britain, Canada, Australia, and South Africa, where no consequential bank failure took place in the depression. Their governments gave no guarantee to depositors. Their economic shocks were as great as ours.

Hoover might also have mentioned Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden, none of which had either deposit insurance or a banking crisis during the ’30s. According to Richard Grossman (1994), although the examples of France and Belgium showed that the presence of banks with extensive branch networks was no guarantee against crises, other things equal, banking systems characterized by fewer, larger banks with extensive branch networks tended to be considerably more stable than others.[5]

That uninsured banking systems could be stable explains the fact that, apart from the United States and Czechoslovakia, no other nation chose to guarantee its banks’ deposits until the 1960s, and only a score had done so as late as 1980. Furthermore, those that opted for insurance didn’t necessarily do so because their banking systems had proven unstable without it. Canada, for example, decided to establish its Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation in 1967 even though no Canadian commercial bank had failed since 1923, and none was then in danger of failing.

Nor does the spread of deposit insurance since the 1960s appear to have occurred in response to policymakers’ perception that their banking systems were at risk of failing without it. Instead, many nations appear to have jumped on the deposit insurance bandwagon either because (mostly U.S.-trained) economists at the World Bank and the IMF pressured them to do so (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008) or simply because doing so had become fashionable (Demirgüç-Kunt and Detaigiache 2002, 1394).[6]

But what about FDR’s claim that deposit insurance was “dangerous”—that, once insured, “the weak banks would pull down the strong ones” (Freidel 1973, 442), as happened in those states that tried insuring banks before the Great Depression?[7]. It turns out that Roosevelt was wrong—for a while. “Despite initial concerns to the contrary,” Eugenie Short and Gerald O’Driscoll (1983, 1) wrote in the early 1980s,

the federal deposit insurance system has worked remarkably well in reducing the number of bank failures and in eliminating depositor loss. The total number of insured bank failures since 1933 has not greatly exceeded the average number of bank failures in any single year during the 1920s… . Moreover, between 1933 and 1982, nearly 99 percent of all deposits in insured banks that failed were recovered by depositors.

But just as Short and O’Driscoll were saying this, serious cracks were forming in the deposit insurance edifice; and soon what once seemed like a banking Arcadia would appear to have been a fool’s paradise. Short and O’Driscoll were themselves well aware of what was happening. The FDIC, they recalled (ibid., 1-2), was part of a package of regulations, the other parts of which—prohibiting banks from underwriting securities and limiting the interest rates they could pay on deposits— served, together with barriers to branching and other constraints on competition, to reduce banks’ incentives and ability to attract insured deposits by taking on greater risks.

However, as rising inflation and interest rates, increased international competition, and the rise of money market mutual funds, took an increasing toll on regulated depository institutions during the 1970s, regulators felt compelled to start peeling risk-constraining regulations away while simultaneously boosting insurance coverage. In particular, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (DIDMCA) of 1980 and the Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982 encouraged excessive risk taking by phasing-out deposit rate limits while raising both FDIC and FSLIC insurance coverage from $40,000 per account, where it had been set since 1974, to $100,000 (Keeton 1984; Bundt, Cosimano, Halloran 1992)

This combination of relaxed regulations and increased explicit insurance coverage, coupled with the implicit insurance of banks regarded as “too big to fail,” created just the sort of dynamics Roosevelt and other critics of deposit insurance feared, with the sad twist that reforms they had seen as better ways to strengthen the United States banking system, such as allowing banks greater freedom to branch, would now also allow them to compete more aggressively for under-priced, insured funds to invest in risky assets. Soon enough, weak banks, including some very big ones, were toppling, and pulling down, not just stronger ones, but their insurers.

For the FDIC, the reckoning took the form of what one of its publications describes as “an extraordinary upsurge in the number of bank failures” between 1980 and 1994 that put extraordinary strains on its resources, eventually costing it $36.6 billion (FDIC 1997, i, 3). But that was nothing compared to what happened in the $617 billion savings and loan industry. There, after breaking yet another batch of state-run insurance schemes, moral hazard problems put paid to the FSLIC as well, thanks to regulators’ willingness to allow insolvent institutions to keep trying their luck while using accounting gimmicks to boost their reported net worth (Kane 1992). The result was scads of high-risk gambles by S&Ls whose owners had nothing to lose that left the industry even deeper in the red, bankrupting the FSLIC and making it necessary for taxpayers to cover $132.1 billion of failed S&L’s $160.1 billion in insured deposits. Though it wasn’t actually “impossible” for the Treasury to pay that bill, it was certainly proof enough of the danger Roosevelt warned against.

It was, ironically, just as these events were unfolding in the United States that national deposit insurance schemes started to proliferate elsewhere. By the summer of 2018, 107 countries had joined the deposit insurance craze. Most have since struggled with moral hazard problems, with depositors losing their incentive to look out for risky banks, and banks taking greater risks in turn. In dozens of cases, where insurance coverage has been high and supervision lax, instead of enhancing banking-system stability, insurance has done just the opposite, “increas[ing] the likelihood of bank crises significantly” (McCoy 2007, 423; see also Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache 2000 and Anginer and Demirgüç-Kunt 2018). This, too, must be accounted part of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act’s legacy.

***

So, we come back to the question, “How much credit does the New Deal deserve for ending the Great Depression?” and, in particular, “How much credit does FDR deserve for the decision to insure bank deposits?” The answer, I think, is that he deserves much less credit than he’s often given. Much less credit; and absolutely no blame.

Continue Reading The New Deal and Recovery:

Intro

Part 1: The Record

Part 2: Inventing the New Deal

Part 3: The Fiscal Stimulus Myth

Part 4: FDR’s Fed

Part 5: The Banking Crises

Part 6: The National Banking Holiday

Part 7: FDR and Gold

Part 8: The NRA

Part 8 (Supplement): The Brookings Report

Part 9: The AAA

Part 10: The Roosevelt Recession

Part 11: The Roosevelt Recession, Continued

Part 12: Fear Itself

Part 13: Fear Itself, Continued

Part 14: Fear Itself, Concluded

Part 15: The Keynesian Myth

Part 16: The Keynesian Myth, Continued

Part 17: The Keynesian Myth, Concluded

Part 18: The Recovery, So Far

Part 19: War, and Peace

Part 20: The Phantom Depression

Part 20, Coda: The Fate of Rosie the Riveter

Part 21: Happy Days

Part 22: Postwar Monetary Policy

Part 23: The Great Rapprochement

Part 24: The RFC

Part 25: The RFC, Continued

Part 26: The RFC, Conclusion

Part 27: Deposit Insurance

_____________________

[1] To this list we might add a fourth item, noted by Golembe in a subsequent interview, to wit: that the deposit “insurance” provided for by the 1933 Banking Act wasn’t really insurance at all. Unlike genuine insurance policies, it covers depositors for losses regardless of whether the losses were due to recklessness on their or their banks’ part. And unlike genuine insurance funds, the FDIC’s insurance “fund” is an accounting fiction, the truth being that the “premiums” it collects from banks go into the federal government’s general coffers. “The government’s guarantee of deposit,” Golembe explains, “was given the name ‘insurance’ because that sounded much less radical than ‘guarantee.’ … [M]any of the bold initiatives of the New Deal were characterized originally as ‘insurance’ in order to make them more acceptable, such as: ‘flood insurance,’ ‘old age insurance’ or ‘crop insurance.’ The problem with calling it ‘deposit insurance’ which it clearly is not, is that some bankers and most academics began to believe it!” For a humorous take on the FDIC’s insurance fund by one of its former chairs, go here and scroll down a bit.

[2] The 1933 Act did away with double liability for national bank shares issued after its passage, but left it in place for outstanding ones. The 1935 Banking Act allowed any bank to exempt all its shareholders from double liability six months after it publicly announced its intent to do so. Most state bank regulators also did away with double liability during the depression. Jonathan Macey and Geoffrey Miller (1992, 32 and 61) argue, compellingly, that double liability had in fact proven “remarkably effective at protecting bank creditors, including depositors,” and “that the nation took a wrong turn” by replacing it with government-administered deposit insurance.

[3] In the deposit insurance context, “moral hazard” refers here to the tendency of depositors to take advantage of having their deposits insured by placing them with relatively risky banks. “Adverse selection” refers to the tendency of riskier banks to be most likely to lobby for, join, and stay enrolled in, deposit insurance schemes.

[4] Some Mississippi banks had branches, but only in the same town or city as their head office. Washington provided for branching from 1907 to 1920, when it also prohibited the establishment of further branches.

[5] Significantly, Grossman (1994, 674) also found that “despite anecdotal evidence and the great stress placed on its importance in the literature,” the extent of central bank last-resort lending was not an important determinant of banking system stability.

[6] Another contributor to the multiplication of deposit insurance schemes during the 1980s and 1990s was the publication, in June 1983, of Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig’s famous article, for which they recently won the Bank of Sweden prize in Honor of Alfred Nobel, purporting to offer a rigorous, theoretical case for such insurance. Because it assumes that banks make only safe investments, while depicting bank runs as random events, the Diamond-Dybvig theory implies that any uninsured banking system might fall victim to runs at any time, without allowing for any adverse effects of insurance. It, therefore, makes insurance seem like a no-brainer. Apart from the dubious assumptions that inform it, the Diamond-Dybvig model has many other serious shortcomings, which I review here and here.

[7] Though there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence of moral-hazard problems in all of the state-sponsored insurance arrangements, Kansas’s has been especially well documented for the Kansas case. See Alston, Grove and Wheelock (1994); Wheelock and Wilson (19942), and Wheelock and and Wilson (1995).

The post The New Deal and Recovery, Part 27: Deposit Insurance appeared first on Alt-M.