Because this series is about the New Deal’s contributions to economic recovery, it’s essential that we recognize the difference, as Roosevelt himself did, between recovery on one hand and relief and reform on the other. A New Deal policy that undoubtedly offered relief to those harmed by the depression, or one that achieved reforms with indisputable long-run benefits, might not have made the depression any shorter, and might even have lengthened it.

But some New Deal policies that had relief or reform as their most obvious aim could also hasten recovery. Any policy that meant more federal spending, and deficit spending especially, might do so simply by boosting aggregate demand, though Roosevelt himself wouldn’t have thought so until well into his second term. Nor was this the only possible way in which the lines separating the R’s could become blurred.

None of the Roosevelt Administration’s 100-day initiatives illustrates this point better than the creation, on June 13, 1933, of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a relatively small and little-known New Deal agency that was only active for just over two years and was wound-up altogether in 1951. In recommending the HOLC bill to Congress two months earlier, President Roosevelt explained that its immediate purpose was “to protect small home owners from foreclosure and to relieve them of a portion of the burden of excessive interest and principal payments incurred during the period of higher values and higher earning power.” But he first let Congress know that he considered the legislation an “urgently necessary step in the program to promote economic recovery.”

The HOLC has been called “one of the great success stories of the New Deal” (Carrozzo 2008, 22), and this opinion is widely shared. Nor is it difficult to see why: during its brief life, the Corporation refinanced mortgage loans for a million homeowners, sparing many the extreme hardships of foreclosure. Lenders benefited as well by trading their delinquent mortgages for the Corporation’s bonds. Yet instead of operating at a loss, the HOLC appeared to turn a tidy profit of $14 million!

In short, no other New Deal program seemed to deliver more obvious benefits at so little cost. But as we’ll see, although the relief the HOLC offered homeowners was palpable, it was mortgage lenders who benefited most from the bargains it struck. That this was so was a reflection of the HOLC’s overarching purpose of promoting recovery. Even so, the Corporation’s contribution to ending the Depression has proven difficult to pin down, and many say that its endeavors had far-reaching long-run consequences that were anything but benign.

Up, Up and Away…

To understand the severity of the Great Depression mortgage crisis, it’s necessary to step back in time to consider the housing boom of the 1920s, and the nature of the mortgage loans that financed a large part of it.

“In a decade of almost steady growth,” Eugene White (2014, 117-18) says, “the behavior of residential construction stands out.” Whereas the better-known boom of the first decade of the 2000s witnessed the construction of 1.3 million new homes, that of the 1920s, when the population was little more than a third as great, witnessed twice that number. For four years starting in 1924, residential construction accounted for more than 8 percent of the nation’s GNP (Field 1992, 785); and during 1925 and 1926 alone, the amount invested in new houses—almost $10 billion—was about equal to the value of new securities purchased in the peak stock market years of 1928 and 1929.

To some extent, the housing boom of the 20s was just the economy’s way of making up for the “crowding-out” of residential construction during WWI, when the government’s heavy borrowing left little aside for the financing of new homes. But according to White (ibid., 125), there was more to the boom than that. As happened during the 2000s, easy Fed policy, lax underwriting standards, equally lax bank supervision, and a roaring but heedless market for securitized mortgages, all played their part, by making it easier than ever for people to buy homes on credit.

…in Not-So-Beautiful Balloons

“Mortgages,” White (ibid., 134, 138) explains, “supplied over $2 billion of the $3.3 billion in financing for 1926,” which was about twice the 1922 level; and almost all of them were short-term, non-amortized mortgages, a type seldom seen either before the First World War or since the Second. Most commercial bank mortgages had terms of 5 years or less, at interest rates of 8 percent or more. Borrowers made interest-only payments until the loans matured, when a final, “balloon” payment, consisting of the loan principal, fell due; and because many were in no position to make that large payment so soon after taking out their loans, refinancing at least once, and often several times, was common.

But by far the most important institutional mortgage lenders in those days were parvenu building and loan associations (B&Ls). These were typically small, local institutions, mutually owned by their members and funded by members’ dues, that is, by their weekly or monthly purchases of association shares (Fishback et al. 2013, 12). B&Ls first rose to prominence during the last decades of the 19th century, thanks in part to relatively strict limits on mortgage lending by commercial banks: until 1914, national banks weren’t supposed to offer mortgages at all[1]; and the mortgages they offered afterwards, as well as those to be had from state banks, featured not only short terms but hefty minimum down payments (Price and Walter 2019, 2).

But the rise of B&Ls before 1900 was nothing compared to what came afterwards. Between 1910 and 1929, their numbers more than doubled, from 5,869 to 12,342, while their assets quadrupled. When the stock market crashed in October 1929, roughly one American in ten was a B&L member; and even in 1930, as the economy was starting to spiral downward, B&Ls were writing 1,000 mortgages a day, and accounting for as much outstanding residential mortgage credit as commercial banks, life insurance companies, and mutual savings banks combined (Mason 2004, 61; Rose 2011, 1076).

Although it resembled other mortgages in being non-amortizing, the standard B&L mortgage had a somewhat longer term—usually between 5 and 10 years. And instead of ending with a balloon payment equal to the loan principal, it allowed borrowers’ share accounts to serve as sinking funds for their loans. When the value of a borrower’s shares, augmented by occasional dividends, reached that of the loan principal, the loan was considered paid. Share accumulations beyond that were the homeowner’s, free and clear.

Thus, like those who took out interest-only mortgages with balloon payments, and unlike today’s holders of amortized mortgage loans, B&L borrowers owed the entire principal of their loans for the loans’ full life. It follows that, if a member defaulted, he or she “lost not only the house but also the accumulated value in the sinking fund” (Fishback et al. 2013, 14-15). Even so, as long as the value of a B&L’s shares stayed the same or rose, these were attractive terms. Borrowers could then avoid having to come up with lump-sum balloon payments, while enjoying a share in their association’s profits. And so they did throughout the 1920s. Only if share prices fell could things possibly turn sour.

That Sinking Feeling

It’s tempting, with the aid of 20/20 hindsight, including knowledge of just how much mortgage-financed home buying went on during the 1920s, to suppose that B&Ls and other mortgage lenders that came to grief afterwards did so because they’d lent recklessly. It’s tempting; but it’s hardly fair, for had it not been for the unprecedented severity of the downturn, most of their loans would have performed well, and their capital would have sufficed to protect them against those that didn’t.

In fact, two things had to go terribly wrong to cause the U.S. mortgage industry to suffer as it did. One was a collapse in house values; the other was a collapse in household income and wealth. Had house prices remained stable, those who could not afford to keep paying their loans at least had the option of selling their properties at prices that would allow them to pay their debts; and if they didn’t, their lenders might make themselves whole by foreclosing. If, on the other hand, house prices fell dramatically, but their owners’ earnings didn’t, though owners would suffer a loss of equity, they could still go on paying off their debts (Wheelock 2008, 1378).

The Great Depression was great in part because, in the United States at least, it managed to pull this “double trigger,” dealing a mortal blow to mortgage lenders by making it impossible for vast numbers of their clients to continue paying off their loans (Fishback et al. 2013, 19). Between 1929 and 1933, house prices fell by a third, while the unemployment rate rose to 25 percent. In 1932, roughly 273,000 people lost their homes, as compared to only 6,000 in 1926. Yet the bottom still hadn’t been reached. By the time of Roosevelt’s inauguration, with roughly a third of all U.S. mortgages in default, and twice as many in arrears, lenders were foreclosing on 1000 loans every day.

This explosion of foreclosures was more than enough not just to ruin many mortgage lenders but to put paid to private firms that insured their loans (White 2014, 141). And the rot was tragically self-reinforcing: as mortgage credit dried up, borrowers facing balloon payments they couldn’t afford would find it impossible to refinance. So more borrowers would default, and more lenders would fail, in a vicious downward spiral. Finally, homeowners who managed somehow to keep up with their payments were paying with dollars worth a third more than their value in 1929 (Fishback et al. 2013, 29).

A similar negative feedback loop was tearing apart building and loan associations, which were all the more vulnerable by virtue of having mortgage lending as their bread and butter. Although their member-borrowers didn’t face balloon payments, so long as many failed to make payments, because they lost their jobs or were earning much less, all their members saw their share values dwindle, and their hopes of paying off their loans go up in smoke. When their B&L’s failed, they were wiped out altogether, and by 1933, almost 2000 of the nation’s 13,000-odd B&Ls had done so (ibid., 30).[2]

Nor was the damage limited to homeowners and real estate lenders. The troubles of the mortgage industry contributed to the overall collapse in spending on residential construction, which (assessed in inflation-adjusted terms) would take almost a quarter-century to return to its 1926 peak (Field 1992, 787). As construction fell to a mere trickle, hundreds of thousands of workers joined the ranks of the unemployed and, in many cases, those of mortgage deadbeats: all told, between a quarter and a third of workers unemployed during the depths of the Depression came from the building trades. So the number of foreclosures also grew, adding that many more housing units to an already severe glut.

Yet hundreds of thousands of nonperforming mortgages were still on lenders’ books, thanks to state foreclosure moratoriums, or to some combination of lenders’ voluntary forbearance and their unwillingness to take possession of more unsaleable real estate. These were, however, mere stays of execution: barring some other intervention, the mortgage pipers would have to be paid, and that many more delinquent homeowners would come home to find their locks changed and their belongings on the street.

A White Knight for Homeowners

Homeowners’ and mortgage lenders’ desperate straits cried out for some sort of remedy. The Federal Home Loan Bank Act, passed in July 1932, was supposed to have helped. Besides granting credit to illiquid B&Ls, much as Federal Reserve Banks granted it to commercial banks, the new Home Loan Banks could also lend directly to distressed homeowners. However, their terms were so conservative that of the 41,000 applications they received, only three were approved! (Carrozzo 2008, 9). The Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) itself recognized the need for an alternative. So when Roosevelt proposed a new agency, to be overseen by the FHLBB, but with the specific aim of giving distressed homeowners a real break, while helping mortgage lenders as well, the House approved it with a whopping 383–4 majority, and it breezed through the Senate on a voice vote.

The HOLC’s plan was ingenious in its simplicity. The Corporation would invite distressed mortgage holders to apply to it for amortized 15-year mortgages, for which it charged a below-market rate of 4.5 or 5 percent. Once it accepted an application, which it did provided it was convinced that the prospective borrower was both capable of making the lower payments and in need of help, the Corporation would contact the lender holding the original mortgage, offering to swap its own bonds, paying 4 percent interest, for it. Although 4 percent wasn’t much, it was a good return compared to what the mortgages in question were actually earning, which was typically nothing at all; it was also likely to be a better deal than what lenders could expect to earn by foreclosing on delinquent properties and then renting or selling them. If the HOLC’s offer was accepted, it would proceed to refinance the loan, charging just $35 in closing costs. Thus most HOLC loans were actually financed by the private-market lenders whose own loans they own replaced.

But for all its simplicity, the HOLC’s plan was no perpetual motion machine: what ultimately kept it humming—and the reason why no private-market effort could have matched it—was the backing it got from the federal government. That backing consisted, not only of the $200 million in starting capital the HOLC received from the Treasury, but of the fact that the federal government guaranteed, first the interest on the Corporation’s bonds and, starting in April 1934, the principal as well. That made those bonds as safe as Treasury securities (Fishback et al. 2013, 112). This meant that holders of HOLC bonds didn’t have to worry that, by being too generous in its lending, the Corporation could itself go bankrupt.

Thanks to those guarantees, the HOLC’s offers were eagerly swooped up. Between June 13, 1933 and June 27, 1935, when it stopped accepting them, it received applications from almost two million homeowners, and by 1936 it had refinanced a million of their mortgages. Most of the homeowners it helped were two years or more in arrears not only on their loan payments but also on their property taxes, which their HOLC loans also covered. It’s therefore likely that, had it not been for the HOLC, they would have lost their homes, doubling the number of foreclosures. That the HOLC wasn’t being too strict in deciding who to help is evident enough from the fact that it ultimately had to foreclose on some 200,000 of its own clients, despite making every effort to avoid doing so. The chart below, reproduced from Fishback et al. (2013, 22) shows the progress of private and HOLC foreclosures.

Four-fifths of those who received HOLC loans were, on the other hand, able to stay in their homes for good thanks to them; and there can be no gainsaying the tremendous value of that deliverance. “The contributions of the HOLC,” Peter Carrozzo (2008, 22) writes, “were very real.” Thanks to it,

[o]ne million families were not afraid to receive their mail each day for fear off the eviction notice; one million families did not suffer the humiliation of carrying furniture and belongings out of their homes as neighbors watched; one million families were not forced to remove to a different neighborhood, into cramped houses with relatives and to transfer children to new schools; one million families did not have their credit destroyed and a sense of utter failure… .

And a Bailout for Lenders

It would be a mistake, though, to treat homeowners as the HOLC’s sole, or even its main, beneficiaries. In fact, as Jonathan Rose (2011, 1074) points out, it was, in important respects, not a borrowers’ program but “a lenders’ program.” For that reason, the HOLC put less emphasis on achieving principle reductions for borrowers than on offering their lenders generous prices for their mortgages, which it did by appraising mortgaged properties very generously. This made it a lot easier for lenders to take part in the program, while also boosting the number of qualified loan applicants. But it also reduced the number of distressed borrowers whose high loan-to-value ratios would otherwise have inspired HOLC efforts to get lenders to agree to “haircuts” on amounts they were owed

Why did the HOLC take this approach? The explanation resides in its double-barrelled purpose. Had relief been the Corporation’s sole aim, it might have preferred to devote more effort toward reducing distressed homeowners’ debt burdens by striking harder bargains with their lenders. But because it was supposed not only to offer relief but to stimulate recovery, it chose instead to increase the relief it offered lenders by, in effect, boosting their capital, much as the RFC boosted the capital of commercial banks. The hope was that doing so would help revive investment in the real estate market.[3] “HOLC officials,” Rose (2011, 1095) says,

appear to have been more concerned with the course of the housing market than with the availability of principle reductions. The most likely rationale was that even if borrowers debts remained high, a strong housing recovery would allow borrowers to gain equity in their properties, and so the HOLC took as its mission to support such a recovery by increasing the size of the program.

But just how did the U.S. housing market respond to the HOLC’s support? Most assessments of the Corporation’s success refer only to the relief it offered homeowners, neglecting its overriding, macroeconomic purpose. Nor is it hard to see why. As David Wheelock (2008, 144) notes, “It is difficult to determine the extent to which the HOLC contributed to a rebound in the housing market, let alone to the macroeconomic recovery.” Wheeler himself claims that, by taking one-million bad loans off of private lenders’ books, the Corporation must have helped revive private mortgage lending. But the extent to which it did is anything but unclear.

A student publication (Hanes and Hanes 2002, 101) says that

By February 1939, the HOLC had refinanced 992,531 loans totaling over $3 billion. The refinanced loans not only halted countless foreclosures but reduced delinquent property taxes. This permitted communities to meet their payrolls for school, police, and other services. Millions were also spent on repair and remodeling of homes. Thousands of men gained employment in the building trade. Thousands more jobs were stimulated in the manufacture, transportation, and sale of construction materials.

But while they all credit the HOLC with avoiding reducing foreclosures, economic historians are not so sure its undertakings led to any substantial change in residential repairs or new construction. In a 2011 study, Charles Courtemanch and Kenneth Snowden (2011) recognize that the HOLC’s “primary goal was to break the cycle of foreclosure, forced property sales and decreases in home values.” They also uncover evidence that HOLC refinancing did indeed “cut short” the vicious cycle of debt deflation of the early 1930s by boosting both home values and homeownership rates (ibid, 309). But they find no evidence that it stimulated new home construction (ibid., 335). In another study published that same year, using data from 2800 U.S. counties, Price Fishback and his coauthors (Fishback et al. 2011) find evidence that the program stimulated both home sales and home and apartment construction, but only after setting data for counties with 50,000 inhabitants or more aside. When bigger counties are included—as seems more appropriate for assessing the program’s overall effects—the HOLC doesn’t appear to have made any difference. Finally, although it’s certainly true that the HOLC spent money repairing homes it foreclosed upon, private lenders did so as well, for the same reason, to wit: to profit as much as possible from the properties they took possession of.

TANSTAAFL

Whatever the HOLC’s macroeconomic achievements, if it’s really true that, instead of costing taxpayers anything, its refinancing efforts actually helped fill the Treasury’s coffers. And that’s what most assessments of those efforts suppose. Peter Carrozzo (2008, 23), for example, says that “[u]pon congressionally-ordered liquidation in 1951 and a final accounting, the HOLC ultimately turned a slight profit.” In his history of the Corporation, C. Lowell Harriss (1951, 159-62) put that profit at $14 million, apparently by simply subtracting its cumulative capital loss of $338 million from its total operating income of $352 million (Wheelock 2008, 144).

But Harriss’s figure is wrong. According to Fishback and his co-authors (2013, 112-114), if the HOLC’s loan financing activities are considered apart from its other undertakings, and account is taken of all its interest expenses, including the foregone interest on the Treasury’s $200 million investment in it, it actually lost $53 million, or about 1.8% of the $3 billion it lent. Considering the relief those loans provided, this was still a good deal. But if one instead treats economic recovery as the goal of the HOLC refinancing efforts, while relying on econometric assessments of its loans’ macroeconomic consequences, those 53 million dollars look more like money poured down a drain.

There is, furthermore, an important sense in which the HOLC placed a much greater burden on taxpayers than that $53 million figure itself suggests. Thanks to government guarantees, the HOLC was able to borrow for between one and two percentage points less than it would have otherwise have had to pay to acquire all the mortgages it acquired. But because those guarantees put taxpayers on the hook for any substantial losses the Corporation incurred, they amounted to a taxpayer-financed subsidy. Had it not been for this subsidy, and assuming it operated on the same scale, the HOLC’s total losses would have been several hundred million dollars greater (ibid., 2013, 119).

In the event, the gamble the HOLC took with taxpayers’ money paid off: the federal government never had to make good on its bonds (ibid., 119). But things might have turned out much differently. If, instead of staying open until 1951, the HOLC had been liquidated in 1938, it would almost certainly have ended up insolvent, and taxpayers would have been on the hook for substantial losses. On the other hand, as Lowell Harriss (1951, 124) points out, had it waited a few more years to dispose of its properties, instead of selling most before the war started, and the rest by 1944, it really would have turned a tidy profit.[4]

Seeing Red

Many also claim that the HOLC’s activities had costly unintended consequences—consequences that now cast a dark shadow over its more immediate and admirable accomplishments. The Corporation stands accused of having invented, employed, and institutionalized the discriminatory lending practice that has since come to be known as “redlining.”

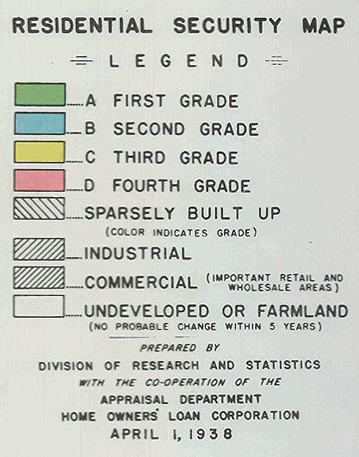

The now-conventional story goes as follows: having been charged by the FHLBB with surveying real-estate risk levels in most larger U.S. cities, the HOLC complied by producing detailed reports on each, together with “security maps” (like the one for Atlanta shown below) for many. Those maps assigned letter grades—A, B, C, and D—to different neighborhoods, while coloring them green, blue, yellow, and red, respectively. Neighborhoods considered likely to appreciate were graded A and colored green; those that had “reached their peak” were graded B and colored blue; those understood to be declining were graded C and colored yellow; and those seen as already fallen, and therefore particularly “hazardous,” were graded D and colored red. Predominantly African American neighborhoods were unfailingly among those colored red.

By basing its own lending on these maps (the story continues), the HOLC systematically discriminated against African American homeowners.[5] Worse still, it shared the maps with both private mortgage lenders and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), which began insuring private mortgages in August 1934, causing them to discriminate against red-zoned African American communities as well.[6] Of course, discrimination and segregation had been rampant long before the New Deal. But redlining reinforced it by making a property’s proximity to minority households a reason for refusing to mortgage it (Faber 2020, 744). Relatively affluent whites, who received almost all FHA-insured loans, were given yet another reason to avoid buying property in predominantly minority neighborhoods, as well as a new, powerful reason to adopt restrictive covenants aimed at keeping African Americans out of white ones. Jacob Faber (ibid, 742 and 763) estimates that, thanks to such discrimination, by 1960 billions had been “funneled…away from poor, urban communities of color, and toward more affluent and suburban white communities,” and roughly two million more African Americans were living in highly segregated city neighborhoods than would have lived in them otherwise.

Whodunnit

Like most widely believed but nonetheless misleading stories, the one blaming the HOLC for subsequent racial discrimination contains a large element of truth. The HOLC did create those multicolored maps; and it did share at least a few copies with the FHA. Furthermore the FHA did methodically and cold-bloodedly discriminate against African Americans; and by doing so encouraged many private lenders to follow its lead. Finally, discrimination played a very large part in perpetuating and intensifying racial segregation.

Where the popular account goes wrong is in blaming the HOLC for what happened. Thanks to more recent research by Amy Hillier, Price Fishback, and others, it appears the agency was mostly if not entirely innocent of the charges laid against it.

First of all, the HOLC didn’t invent discriminatory lending practices. According to Hillier (2003, 398), mortgage companies had long been systematically discriminating against African American neighborhoods when the HOLC was established. More importantly, despite the prevalence of discriminatory lending, the HOLC itself didn’t practice it. On the contrary: it vowed not to put residents of poorer, minority neighborhoods at a disadvantage, and the numerous mortgages it purchased from them leave no doubt that it kept that promise.

As for those notorious multicolor maps, HOLC staff couldn’t possibly have made much use of them in deciding which mortgages the Corporation should purchase, for the simple reason that the maps weren’t drawn until after the HOLC did most of its lending. Like other materials the Corporation produced as part of the FHLBB’s City Survey Program, which was launched in August 1935, the maps weren’t intended to guide its mortgage purchases. Instead, their purpose was to help it “gaug[e] the risks of the enormous portfolio of loans it had already accumulated, and in managing the resale of its foreclose real estate holdings” (Fishback et al, 2022, 3).

The possibility remains that other lenders and government agencies, and the FHA in particular, based their own mortgage approval practices on the HOLC’s security maps. But the evidence for this is extremely slim. The FHLBB treated all City Survey Program materials, including the maps, as highly confidential, precisely because it feared others might interpret and use them in ways “which were not intended” (Hillier 2003, 399). Private lenders never got any copies; and HOLC staff were repeatedly told to keep their own copies to themselves.

The FHLBB did, however, supply security maps to “a handful of government agencies,” including the Federal Housing Authority. But there’s no evidence that the FHA based its own assessment of mortgages’ riskiness, or its willingness to insure them, on those maps. Instead, it had begun developing its own risk rating system, using block-level information and maps based upon the same, eight months before the start of the FHLBB’s City Survey Program. Alas for the HOLC, and to the enduring confusion of many subsequent scholars, it happened to use the very same letter grading system found on the HOLC’s maps.

If circumstantial evidence can also be thrown on the scales in assessing the HOLC’s culpability, that evidence also tends to exonerate it, while making the FHA look as guilty as a cat in a goldfish bowl. The HOLC was charged with keeping distressed mortgage holders in their homes, and it could hardly have done so without making risky loans. Although it did indeed screen-out applicants it considered unqualified, either because they didn’t need its help or because their circumstances made them unlikely to avoid defaulting even on its more generous loans, it had no reason to discriminate against particular neighborhoods or minorities. The FHA, in contrast, was supposed to play it safe. Its goal was reviving the construction of new homes, almost all of which were destined to be sold to relatively affluent, white home buyers, by insuring “economically sound” mortgages only. That meant not insuring mortgages in predominantly African American neighborhoods. It also meant not insuring mortgages—including ones for African Americans seeking to move into mostly white neighborhoods—that reduced the value of others the FHA had insured.

Far from making a secret of its discriminatory practices, the FHA recommended them in early editions of the manuals it supplied to its underwriting staff. Section 920 of the 1938 version, for instance, explains to them that, while

[i]t is not the policy of the Federal Housing Administration to exclude entire cities and towns from the benefits of mutual mortgage insurance…it may be that within certain communities where present day and expected future stability is exceedingly low, only certain favored locations which surpass the general average of the town or community may prove acceptable for insurance. The rating ascribed shall apply to all locations situated in the area rated (my emphasis).

Later in the same manual (§931), the FHA’s underwriters are reminded that

[p]roperties must remain desirable to their present owners if a satisfactory lending experience is to be expected. A change in class of occupancy is frequently accompanied by a decline in the values and seriously affects the continued desirability of the properties to their original owners. Mortgage risk is greater in such neighborhoods.

Should such statements seem too vague to be taken as proof that the FHA understood that its rules amounted to a policy of discriminating against African Americans, we may call on Homer Hoyt, the FHA’s Principal Housing Economist, to dispel any doubt. In another FHA publication, he observes that “the presence of even one nonwhite person in a block otherwise populated by whites may initiate a period of transition” (Hoyt 1939, 54; quoted in Fishback et al., 2022, 3).

Finally, unlike the HOLC maps, many of which are still available, the last copies of the FHA’s security maps were deliberately destroyed by one of its staff members soon after it was served notice, in 1969, of a class action suit brought against it for discrimination (Sagalyn 1980, 16; Fishback et al. 2022). In a court of law, this would qualify as evidence of “consciousness of guilt.” Because such evidence is also circumstantial, a judge might advise jurors to infer nothing from it. Nothing, that is, that isn’t reasonable, given other evidence.

Continue Reading The New Deal and Recovery:

Intro

Part 1: The Record

Part 2: Inventing the New Deal

Part 3: The Fiscal Stimulus Myth

Part 4: FDR’s Fed

Part 5: The Banking Crises

Part 6: The National Banking Holiday

Part 7: FDR and Gold

Part 8: The NRA

Part 8 (Supplement): The Brookings Report

Part 9: The AAA

Part 10: The Roosevelt Recession

Part 11: The Roosevelt Recession, Continued

Part 12: Fear Itself

Part 13: Fear Itself, Continued

Part 14: Fear Itself, Concluded

Part 15: The Keynesian Myth

Part 16: The Keynesian Myth, Continued

Part 17: The Keynesian Myth, Concluded

Part 18: The Recovery, So Far

Part 19: War, and Peace

Part 20: The Phantom Depression

Part 20, Coda: The Fate of Rosie the Riveter

Part 21: Happy Days

Part 22: Postwar Monetary Policy

Part 23: The Great Rapprochement

Part 24: The RFC

Part 25: The RFC, Continued

Part 26: The RFC, Conclusion

Part 27: Deposit Insurance

Part 28: A New Deal for Housing

_______________________

[1] But see Keehn and Smiley (1977, 475), who draw attention to “the numerous methods that national banks used to grant loans secured by mortgages and real estate” despite the prohibition.

[2] Delinquent loans weren’t the only reason B&Ls were dropping like flies. Another was competition from postal savings banks. According to Sebastian Fleitas, Matthew Jaremski, and Steven Sprick Schuster (2023, 16), during the Depression the postal savings banks, deposits at which were fully insured, “stripped funds from B&Ls.” They claim that, had it not been for competition from their government-run rivals, “B&Ls would have maintained a significantly larger number of investors and may have been able to expand lending during the period” (ibid., 16). See also O’Hara and Easley (1979).

[3] Rose (2011, 1094) claims to “find little support” for the claim “that HOLC officials set out to indirectly recapitalize mortgage lenders,” while proposing instead that their goal was “increasing [lenders’] participation.” I frankly cannot see any reason for his treating these as alternative hypotheses: whether HOLC officials thought in terms of recapitalizing lenders or not, it was only by offering to do so, at least implicitly, that they succeeded in gaining their cooperation.

[4] According to a consistent index constructed by Jonathan Rose (2022, 917), using data from repeat Baltimore home sales, between 1939 and 1945 house prices more than doubled, even surpassing their mid-1920s peak. Rose finds, furthermore, that the same price data “show no meaningful recovery until the onset of World War II.” There is therefore no reason to assume that the HOLC’s activities themselves played a part in boosting Baltimore house prices.

[5] Although the conventional story’s locus classicus is Jackson (1980; see also idem. 1985, 197-203), Kenneth Jackson’s own telling of it recognizes that the HOLC did not itself discriminate against minorities or poor neighborhoods, whereas many subsequent tellings do not. Namrata Singh (2022), for example, writes that the HOLC “directly and explicitly biased its decisions on the basis of a neighborhood’s racial composition” and that it “discriminated against black populations the most blatantly, but also considered Jewish, Catholic, and many immigrant populations, particularly those from Asia and Southern Europe, to be undesirable and high risk.”

[6] The FHA, one of several results of the June 27, 1934 National Housing Act, was the New Deal’s other, major housing market initiative. Apart from discussing its part in institutionalizing redlining, I pass over it because I share the consensus view of economists, succinctly stated by Alexander Field (1992, 794), that its “activity in the 1930s had a comparatively modest immediate or direct influence on the housing industry” and that “like so much of the New Deal, its real significance would be experienced after the war”—that is, after the economy had recovered from the Great Depression. According to Grebler, Blank, and Winnock (1956, 148), although it’s likely that FHA insurance “helped to accelerate the expansion of residential building” before the war, it’s also true that much of the construction financed by FHA-insured loans “would probably have occurred without them.”

The post The New Deal and Recovery, Part 28: A New Deal for Housing appeared first on Alt-M.