Paul Matzko

Former FCC Chairman Newton Minow died a few days ago and outlets dug deep into their archives to dust off their pre‐written obits for the 97‐year‐old who lived a full and eventful life. I had the opportunity to be on a panel with Minow back in 2021, which was a somewhat surreal experience given how few of the people that I covered in my book on broadcasting in the 1960s are still around. I have a few thoughts about his legacy to share with you.

Let’s start with a positive note. Minow often had solid foresight. For instance, he was right when he told JFK that launching the first telecom satellite in 1962 was a bigger deal than landing a man on the moon. We’ve since sent twelve men to the moon and might eventually send more. But in terms of the effects on our everyday lives, manned moon missions pale in comparison to the 11,139 satellite launches over the same time period (and the prospect of tens of thousands more in the near term).

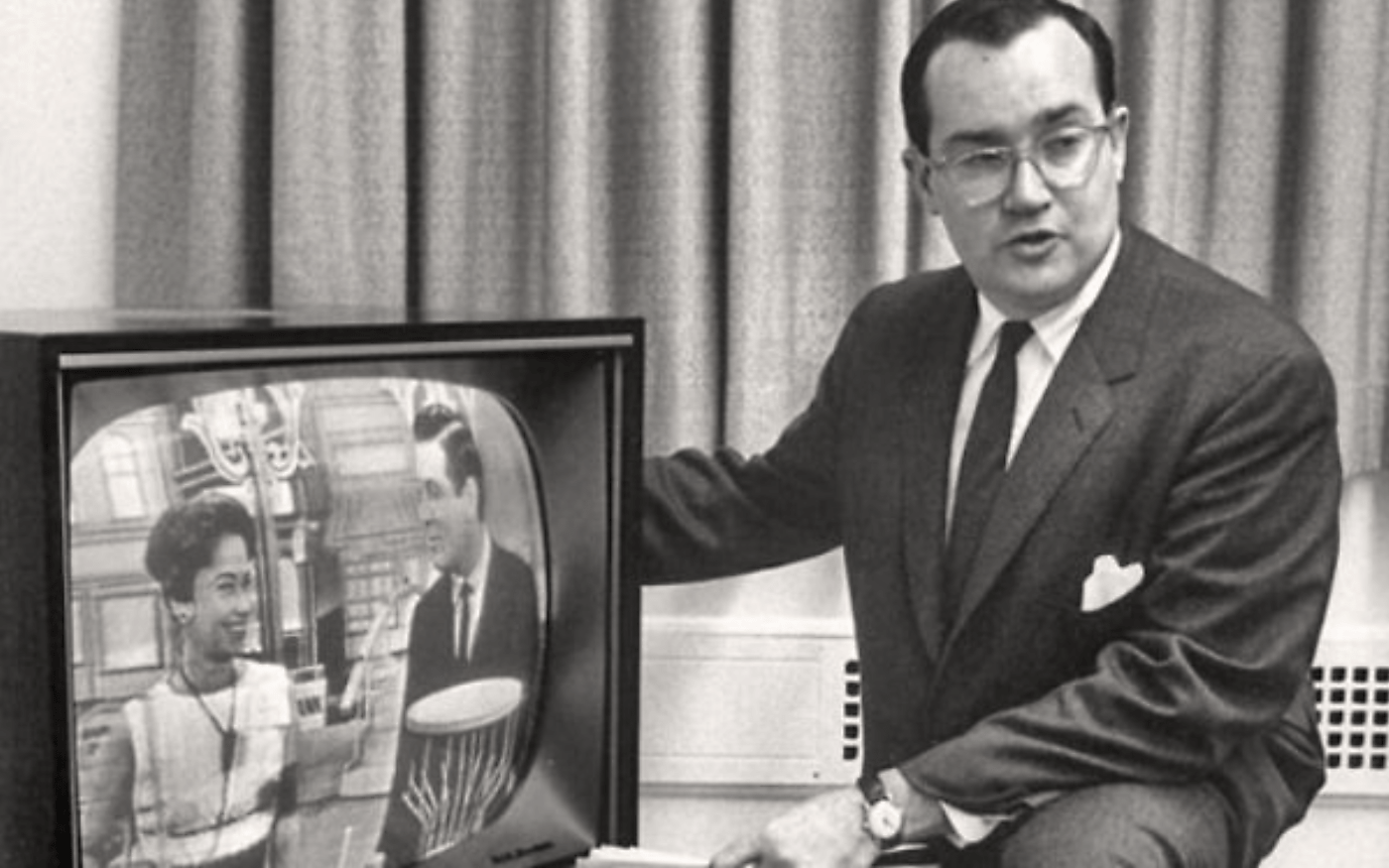

But that’s not what Minow is generally remembered for, although the fact that he is remembered at all is remarkable given how few FCC commissioners that even relatively well‐informed members of the public are familiar with. Minow’s legacy is inextricably linked with the only speech in the history of the FCC that managed to worm its way into the public consciousness, when in 1961 he declared that television was a “vast wasteland” full of “blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder,” westerns, gangsters, and cartoons.

Minow’s proposition that tv was a “vast wasteland” became the implicit framing for much television regulation over the next half century, including the creation of public television. He believed that commercialized television programming was not just subpar but actually dangerous, especially to children. As he testified to Congress in 1991, “In 1961 I worried that my children would not benefit much from television, but in 1991 I worry that my grandchildren will actually be harmed by it.”

In this regard, Minow was very much a man of his time, his views an artifact of the counter‐counter‐cultural moral panics of both the 1960s and 1990s. Tipper Gore complained about metal music and hiphop to Congress, and we got parental warning stickers on cassettes. Minow worried about children seeing “25,000 murders” on tv before turning 18, and we got V‑chips in all our tvs. (No kidding; your tv still has one.) And there is an echo of this kind of technocratic nanny‐Statism in the ongoing debates over imposing new regulations on the internet, like prohibiting targeted advertising to impressionable youths or even banning their access to social media entirely.

It’s worth reflecting on the two core mistakes that Minow made — and which his politically progressive but temperamentally conservative descendants often continue to make — when it comes to mass media. First, he was (mostly) wrong to call television a vast wasteland in 1961. Entertainment is good, actually. In his famous speech, Minow doesn’t bother actually *proving* that entertainment is harmful to children; he simply assumes that his audience will agree with him. And yes, there will always be cultural critics like Minow and Neil Postman who worry about the vulgar amusements of the common man, but I think they mistake their personal preferences and antipathies as representative of the public interest.

Bear in mind that television in 1961 was still a young medium. It wasn’t until 1954 that a majority of American households even had a television. Parents responded in predictable fashion to a new technology popular with their children, both grateful for the break as their kids watched Howdy Doody and worried that it would rot their minds and morals. It didn’t. There’s strong evidence that moderate consumption of television is not harmful for kids, and even in larger doses any negative effects appear minor and/or correlative.

Of course, Minow couldn’t have known that, and freaking out about new technologies and their affects on children is a rite of passage for parents and bureaucrats alike. In the 18th century, it was novels that were leading children astray by promoting loose morals and lying fictions. In the early 20th century, the “tell‐tale signs of corruption” included well‐thumbed pulp paperbacks that tempted schoolboys to fantasize about flying to alien worlds instead of doing their homework and becoming good, sane, sober citizens. Minow’s style of parentalism is both very old and boringly expected.

And like with novels and pulp fiction, it’s not just that westerns and gangster shows and cartoons are harmless; they can be actively good. Consider the animated Netflix show BoJack Horseman. It’s won award after award for its darkly comedic exploration of the hollowness of fame, struggles with mental health, generational trauma, and the persistence of toxic masculinity. If my son, when he becomes a teenager, were to tell me he’s started watching BoJack episodes, I’d see it as a great chance to both bond with him and do a little parenting as we unpack the sundry issues explored by the show. Yet Minow thought cartoons et al ipso facto valueless, even dangerous. His “vast wasteland” was as much a failure of his own imagination as a reflection of the lay of the media landscape.

Something similar is commonplace with reactionaries today in regards to new media. When policymakers discuss social media, their belief that the medium is (at best) valueless and (at worst) dangerous for teenagers operates on the level of assumption. They rarely bother asking kids what they think. While the adults fret away, teens are busy learning new skills on Youtube, building ad hoc communities on Instagram, and getting their news from TikTok. Between the advent of digital streaming and the rise of social media, teens now live in an unprecedentedly rich information environment. The video landscape is vast, to be sure, and operating at a scale that makes the network television era seem quaint by comparison — but it’s only a wasteland if you have a blind determination to bypass every oasis in sight.

Now, I said Minow was “(mostly) wrong” about the quality of television in 1961 (and in 1991, etc). Television was once a much less interesting and less diverse space. In the 1960–61 season, there were roughly 150 series aired on the big three networks, including more than a few of Minow’s hated westerns (Maverick, Gunsmoke, Bonanza) that are now beloved classics of the era marketed to nostalgic Boomers. And that programming tended to appeal to the lowest common social denominator, which also entailed racial and gender exclusion. My grandfather’s favorite was The Red Skelton Show, an unchallenging sketch comedy rarely accused of pushing social boundaries.

By 2019, including cable and streaming shows, the number of scripted TV series — which, note, is a smaller category — has ballooned to 532 shows. And the sheer diversity of shows would be unfathomable to someone in the 1960s, with content appealing to a much broader range of people and underserved communities than ever before in television history. In this era of peak TV, you could get a queer dramedy about a privileged white woman in prison (Orange is the New Black), the story of a high school teacher Breaking Bad and becoming a drug kingpin at the cost of losing his family, or an alternate history of the United States as scathing critique of patriarchal norms (Handmaid’s Tale). These shows simply could not have been made in the 1960s, when the combined motivations of a network‐dominated industry structure and FCC nanny‐ism incentivized the production of safe, inoffensive, bland tv. Today, we have both more AND better quality television.

This takes us to the second way in which Minow was wrong. Like progressive technocrats are wont to do, spotting a market failure means reflexively turning to a government solution. To be fair, Minow’s favored solution, public media, could have turned out much worse than it did. I am a frequent listener to public radio and grew up watching quite a bit of public television. It is quality content, even if skewed towards the center‐left politics of its original proponents. And it’s notable that the success of public media appears to be in inverse proportion to just how “public” it actually is. American public media is exceptional for how light of a governmental touch is involved compared to other countries’ public media systems.

Regardless, the advent of what we now call the “golden age of television” was all about unleashing market forces. In the decades after Minow’s time at the FCC, one new mass media after another was freed from burdensome government oversight. First, cable broadcasting, which had languished under tight FCC restrictions, was freed from content oversight by the courts in 1977. That led to the cable boom of the 1980s as new channels and programs innovated and diversified.

Then in the 1990s both Congress and the courts decided that the internet should be born free rather than in regulatory captivity. Online content would be regulated more like print than like broadcasting, meaning a much higher degree of First Amendment protection against censorship and regulatory control. That enabled the proliferation of Web 2.0 platforms in the ‘00s and ‘10s, leading to a firehose of user‐produced content.

Honestly, I’m selling the transformation short by focusing on television rather than the new online platforms. The average teenager spends far more time watching Youtube and TikTok than all other platforms combined. The golden age of television is about to be eclipsed by a new era of user produced content, which will only accelerate when AI allows anyone to create any kind of video they are capable of imagining.

Far from a wasteland, the amount and quality of televisual content has never been bigger or better. Every day on Youtube, a third of a waking human lifetime’s worth of videos is being uploaded. In just the last week or so on Youtube, I’ve watched a former NASA engineer explain Rwandan drone tech to my son, seen a longform video essay unpacking the transphobia of JK Rowling, and done the stereotypical dad thing and watched a few WW2 documentaries.

Inasmuch as Minow’s “vast wasteland” was once real, deregulation and digitization have long since flooded the desert.

This essay is crossposted from the author’s Substack. Subscribe for more posts on the intersections between history and policy.