Norbert Michel and Jai Kedia

Testifying before the Senate Banking Committee last week, Fed Chair Jay Powell acknowledged inflation has come down but suggested it hasn’t slowed because of monetary policy. Insisting that the Fed still has work to do to bring inflation down, he told the Committee:

I won’t say [food and energy are] not affected at all by monetary policy, but they’re principally affected by other things in the economy.

Really, where monetary policy takes effect is in the service sector, and that’s where we haven’t seen much progress. Inflation, broadly, is coming down, but as I said in my remarks, we still have a long way to go. Inflation’s still running between 4 and 5 percent.

Powell’s remarks bring up several interesting policy questions. For starters, the Fed does not have any particularly good price setting powers for different sectors of the economy, which is why all economists learn that monetary policy tries to stabilize the overall price level. Put differently, there is no reason to expect the Fed’s tightening to affect only the services sector. Given that service‐based companies are generally less capital intensive than goods‐producing companies, it makes sense that the service sector may be even less responsive – at least directly – to monetary policy changes.

Moreover, from February through April the average monthly change in the services category for Personal Consumption Expenditures is very close to its long‐term average. The long‐term average monthly change, measured from January 1959 to April 2023, is 0.32 percent, while the average change from February 2023 to April 2023 (the three most recent dates available) is 0.35 percent. So, price changes in the service sector have been trending down.

It’s also clear the annual rates of PCE services price increases are elevated at least partly due to the below average changes experienced prior to the COVID crisis. The average monthly change from January 2010 to February 2022, for instance, was just 0.2 percent, while the average from March 2022 to April 2023 was 0.45 percent.

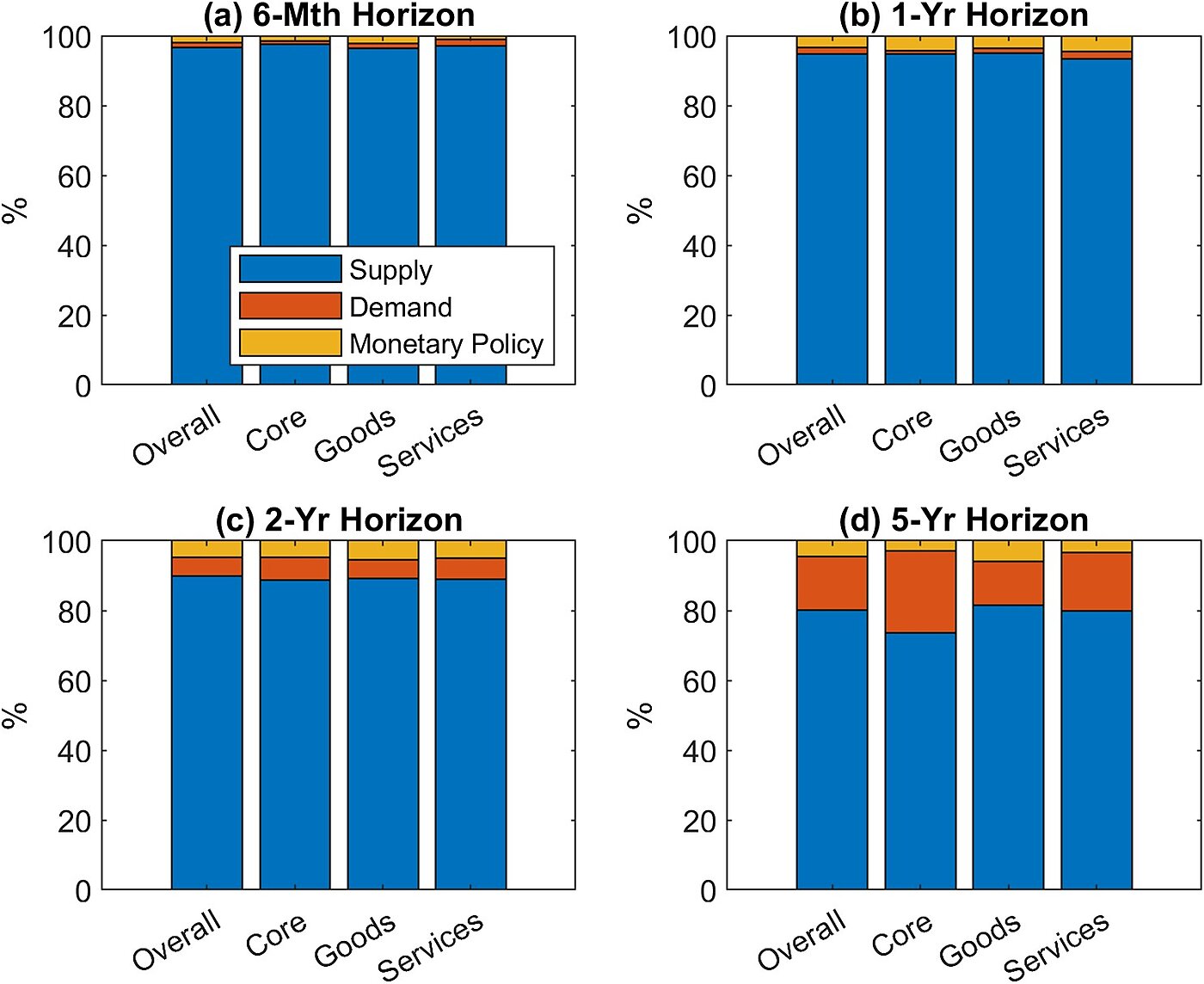

Beyond these simple comparisons of percentages, more sophisticated research suggests that there is little reason to expect monetary policy to have much of an effect on prices in the services industry. As a Cato study using a VAR technique finds, Fed policy has hardly mattered in explaining inflation (services or otherwise). Figure 1 below reproduces the breakdown of inflation into its demand, supply, and monetary policy components from 1960 onwards. As the graph shows, supply factors dominate – they account for over 80% of the variation in service‐sector inflation, both in the short‐term and long‐term. In the near term, monetary policy explains less than 2% of inflation. In the longer term, the effects increase but never account for more than 5% of service‐sector inflation.

If, as some suggest, the Fed tries to rapidly tighten credit conditions now, it would be doing so primarily because the month‐to‐month change in service sector prices remains above its long‐term average. For the last three months, this average change was just 0.027 percentage points higher than its long‐term average. For the previous 12 months, it was only 0.13 percentage points higher.

As we’ve argued before, it seems perfectly reasonable that the members of the Federal Open Market Committee would pause their tightening campaign. As a larger issue, it is unclear why people would want any government agency to have the ability to constrain credit for arbitrary reasons such as those discussed above.

For a detailed analysis, please see this Cato working paper.