Scott Lincicome

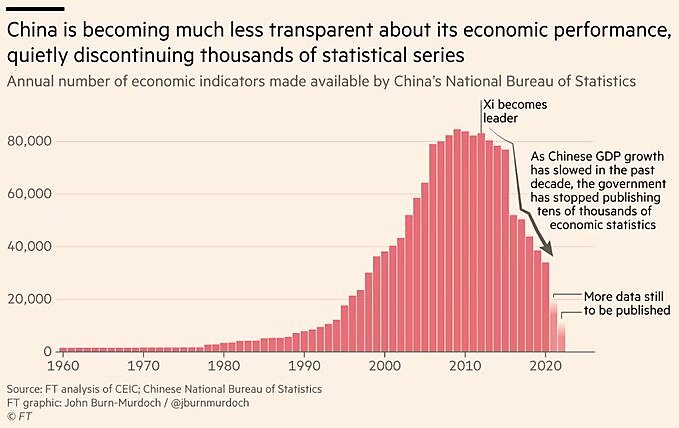

According to various news outlets, the Chinese government has recently stopped publishing information on youth unemployment, deflation, and other statistics that paint a gloomy picture of China’s economy, while also instructing economists in China to “avoid speaking negatively about topics ranging from fears of capital flight to softening prices” and to instead “to present economic news positively in order to increase public confidence.” These moves appear to be part of the longer‐term disinformation trend that, per the Financial Times, began under President Xi Jinping and accelerated in recent months:

As I explained in a column last year, China’s growing transparency issues are not just unsurprising (official Chinese data have long been suspect) but also a fundamental weakness in authoritarian regimes’ economic systems as compared to those of their liberal democratic rivals:

Authoritarian institutions… encourage misinformation from both the bottom up (e.g., local governments or generals) and the top down (e.g., the central government or leader), and they provide government officials with the mechanisms to forcibly restrict countervailing data. This informational vacuum might help a dictator look good (for a while, at least), but it’s obviously problematic for government and private sector decision‐making on economic, military, public health, and other crucial policy matters. Open economies, by contrast, rarely suffer from such an affliction: Even where the state tries to distort or withhold information, private actors (media, academia, think tanks, for‐profit research organizations, etc.) will eventually fill the void. And democratic accountability will probably (again, eventually) make elite leadership pay for any grievous errors.

This systemic weakness, along with several others (see, e.g., this recent column from economist Adam Posen), should give U.S. policymakers and pundits further reason to remain confident in Western democracy and free market capitalism instead of advocating for more “China‐style” industrial policy and similar economic interventions:

In the long term,.. distant history and recent events give us strong reasons to doubt that illiberal strongmen are such a dire threat to the United States as to necessitate abandoning our open, liberal system and embracing illiberalism and central planning ourselves. Time and time and time again, authoritarian regimes’ serious institutional shortcomings make serious problems all but inevitable. And they render the common view of the omniscient authoritarian chessmaster, used to sell so much bad U.S. policy, beyond farfetched.

We liberals have problems too, of course, but our flaws are, importantly, out in the open. Authoritarians’ much bigger flaws are usually hidden.

Until they aren’t.

Hopefully recent events in China make these realities even clearer to those in Washington who have yet to accept them.