Travis Fisher

At the signing of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), President Biden said: “The Inflation Reduction Act invests $369 billion to take the most aggressive action ever — ever, ever, ever — in confronting the climate crisis and strengthening our economic — our energy security.” One year later, the Biden Administration reaffirmed the President’s statement by describing the IRA as “the most ambitious climate action in history.”

President Biden is certainly correct that spending $369 billion on anything is aggressive, even if that level of spending is projected over the next decade. That’s nearly ten times the amount Elon Musk paid for Twitter (now renamed X). However, the cost could be substantially higher than that, and taxpayers could be on the hook to provide that level of subsidy to electricity producers every few years in perpetuity or until the law is changed. That is because the energy subsidies in the IRA are enacted as permanent law, only to expire when specified emissions targets are met. This could mean that some provisions will last well beyond the 10‐year budget window.

After the IRA was passed, the estimate of $369 billion for energy credits over a decade was revised upward. Now we have higher estimates of the cost of preserving the IRA credits for ten years. An April 26, 2023 estimate by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) was $515 billion. An April 2023 Goldman Sachs report estimated that the IRA “will provide an estimated $1.2 trillion of incentives by 2032.”

Why the disparity? It depends on what’s included in the estimates. The report by Goldman Sachs estimated much higher spending on tax credits for electric vehicles than the JCT in part because it projected that more electric vehicles (EVs) would be eligible for the full credit. That is a theme throughout the IRA—eligibility for different amounts of credits depends on several factors (like labor requirements and thresholds for domestic content, etc.). The subjective nature of modeling the IRA’s fiscal cost highlights how little we know about what these energy credits will cost the taxpayer.

Time is Money (a lot of it)

Consider another variable: the amount of time the federal government (i.e., federal taxpayers) will continue to pay subsidies. If we limit estimates of the cost of IRA tax credits to a 10‐year window (standard practice in budget assessments), we get a total of about $515 billion to $1.2 trillion. That is already a wide range, but it’s a lower bound because it fails to account for substantial costs down the road. If we look beyond the 10‐year horizon, the cost of the IRA credits could increase and remain high for years, perhaps indefinitely.

The tax credit for producing electricity from non‐GHG‐emitting sources begins to phase down only when total GHG emissions from the electricity sector fall to 25 percent of the 2022 level (see PDF page 169 here):

(3) APPLICABLE YEAR.—For purposes of this subsection, the term ‘applicable year’ means the later of—

(A) the calendar year in which the Secretary [of Energy] determines that the annual greenhouse gas emissions from the production of electricity in the United States are equal to or less than 25 percent of the annual greenhouse gas emissions from the production of electricity in the United States for calendar year 2022, or

(B) 2032.

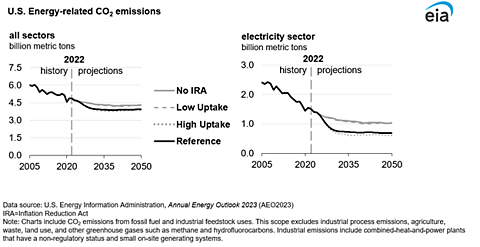

To be clear, a 75 percent reduction in GHGs from the electricity sector could take a very long time, especially since the IRA uses 2022 as the baseline year rather than a higher‐emission year like 2005. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) analyzed electricity sector GHG emissions in the IRA reference case (and in the no‐IRA case) and found neither case to bring electricity sector emissions down to 25 percent of the 2022 level by 2050.

So how long are taxpayers stuck with this tab, and what’s the final tally? One estimate that accounted for the cumulative cost of the IRA credits over a longer period came from the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. In fact, a Wood Mackenzie blog post is the only source I have seen that explicitly stated that IRA energy credits could be indefinite. It said:

Based on the language in the IRA, our view is that these tax credits will be extended for substantially longer than 2032 – perhaps even 30–40 years. Absent IRA repeal, this means that instead of several hundred billion dollars in tax credits for new renewables and storage through 2032, the real money on the table is on the order of trillions of dollars over multiple decades.

With an expanded time horizon, Wood Mackenzie found the cumulative cost of IRA energy credits could reach $2.5 to $3 trillion, most of which would go to utility‐scale solar energy projects. Of course, if EIA is right about the trajectory of GHG emissions from the electricity sector (that emissions will not fall to 25 percent of 2022 levels, even by the year 2050), the cumulative cost could be even higher.

In a forthcoming policy brief, I will analyze the total taxpayer liability in the IRA as established in the statute, and I provide a sensitivity analysis taking into account the key variables involved: 1) the level of the credits based on eligibility criteria, 2) the volume of credit‐eligible electricity generation, and 3) the applicable time horizon (when the electricity sector reaches GHG emissions at or below 25 percent of 2022 levels, which itself depends on many variables such as growth in electricity demand).

Conclusion

The total cost of energy credits in the IRA is an unstable number with no reasonable cap. The energy credits are subject to a wide range of variables, and they could persist for decades. Understanding the implications of the IRA for tax and budget policy requires going beyond the typical 10‐year budget window, as the IRA itself does. Did policymakers mean to subsidize low‐GHG electricity production to the tune of $50–100 billion per year, ad infinitum—easily $2.5–3 trillion or more when all is said and done? Maybe not, but we’ll find out if policymakers want to keep accruing them when these costs start piling up.