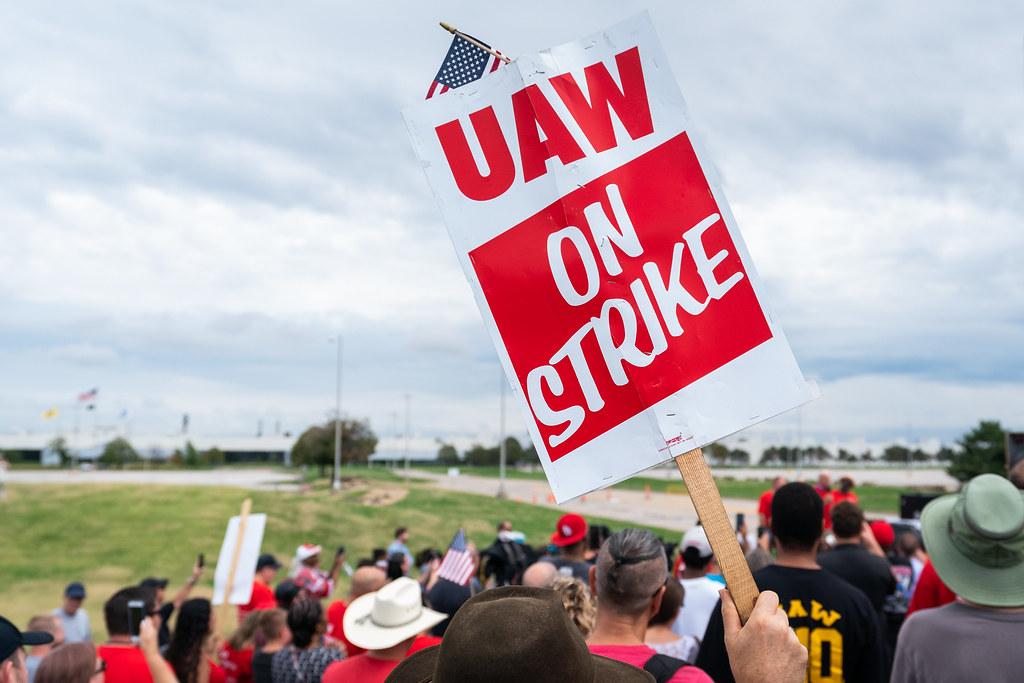

On September 15, 2023, the United Auto Workers (UAW) union staged a massive strike consisting of thirteen thousand workers, and for the first time, the union hit three separate automotive enterprises simultaneously: General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. The Associated Press noted that only three assembly plants are on strike at the moment: a General Motors factory in Wentzville, Missouri; a Ford plant in Wayne, Michigan; and a Jeep factory owned by Stellantis in Toledo, Ohio.

What is the UAW demanding? Another Associated Press article outlined the demands of the UAW and its president, Shawn Fain:

The union is asking for 36% raises in general pay over four years—a top-scale assembly plant worker gets about $32 an hour now. In addition, the UAW has demanded an end to varying tiers of wages for factory jobs; a 32-hour week with 40 hours of pay; the restoration of traditional defined-benefit pensions for new hires who now receive only 401(k)-style retirement plans; and a return of cost-of-living pay raises, among other benefits.

Americans may see these demands as justified, that these workers deserve the privilege of higher pay and benefits. However, they are woefully unaware of the economic consequences that will follow if these demands are meant in full. Historically, unions have been a detriment to all parties both involved and uninvolved with them. President Shawn Fain needs to take a lesson from the failure of John L. Lewis, the president of the United Mine Workers of America.

The Mining Strikes of John L. Lewis

Private sector unions differ from their public counterparts in one significant way; private sector unions cannot rely on taxpayer money. A public school may lose teachers due to poor academic performance, or a police station may lose funding due to charges of brutality, but the government—whether state or federal—will still collect its taxes from its citizens. Because of this, these public sector industries are exempt from taking losses, meaning that these unions don’t have to worry about losing their power.

However, private sector unions—despite having leverage in the government—still need the business they operate in to stay open; otherwise, all the workers they represent will be out of a job. John L. Lewis did not understand this concept when he was advocating for higher wages and benefits for the miners he represented. Thomas Sowell outlined the economic repercussions caused by the strikes and subsequent deals brokered between the coal companies and the United Mine Workers in an excerpt from his book The Thomas Sowell Reader:

John L. Lewis . . . secured rising wages and job benefits for the coal miners, far beyond what they could have gotten out of a free market based on supply and demand. But there is no free lunch. An economist at the University of Chicago called John L. Lewis “the world’s greatest oil salesman.” His strikes that interrupted the supply of coal, as well as the resulting wage increases that raised its price, caused many individuals and businesses to switch from using coal to using oil, leading to reduced employment of miners.

No private business can survive under continued losses; its survival depends on meeting the demands of the consumer. However, when outside influences such as unions negotiate benefits and wages higher than what the market says it should be, the result has to be reduced employment in order for the business to make a profit. If Shawn Fain’s plan succeeds, he just might become the world’s greatest Toyota salesman.

CEO Pay

The major claim of the striking UAW leaders is that Ford’s CEO, Jim Farley, makes too much money. Fortune magazine reported that Mr. Farley made twenty-one million dollars in his last pay package, with eight million considered to be “excess.” To the union, this is seen as exploitation, but they fail to realize how CEOs get paid. The University of Colorado explains that it is the market that decides the salary of a CEO:

Currently, the market mainly sets CEO compensation. This means that there is no cap on how much a CEO can earn. If a company requires a quality CEO, they have to pay what the market is demanding in order to ensure that they can provide a competitive salary to a qualified candidate. This is the main reason that many CEO’s are paid so much more than the average worker—companies need to secure the talent that will help their companies succeed.

Unlike the UAW—which takes two hours pay per month from its members, along with a ten dollar initiation fee—the CEO’s salary depends on the market, on what the stockholders decide and want. The $850 million dollar fund that is available to the UAW certainly didn’t come from the market or any productive means nor will it be used in any productive means. Profits made by companies and CEOs don’t get stuffed under a mattress and forgotten about; it is reinvested into capital. Thomas DiLorenzo’s book The Politically Incorrect Guide to Economics states:

Capitalism cannot grow without capital investment in machinery, tools, equipment, software and so forth. With more kinds of this investment, the workers themselves become more productive, creating more goods and services per hour. . . . So employees, without any additional educational experience, or training, are all of a sudden more valuable to employers. Skilled, reliable employees are always in demand, which means employers are forced by competition to pay their employees more or risk losing them to other businesses.

Conclusion

Labor unions have not been a driving factor in the increase of wages in the United States. In fact, unions have been nothing but a detriment. Unions do not produce anything that will create wealth; they do not innovate. They merely siphon off money made by the taxpayers, from the companies, and from the workers they represent.

Simply put, increases in the standard of living have been possible only through heightened productivity sparked by capital investment and innovation. If Shawn Fain and the UAW don’t comprehend the economic reality of their demands, they will likely be shocked by the inevitable consequences the strikes will bring.