James A. Dorn

During Mao Zedong’s rule, there was no private housing. All private property was deemed illegal and against Marxist principles. The failure of communal property led to experiments with various forms of ownership under Deng Xiaoping. Today private ownership of housing is widespread, accounts for about 25 percent of China’s GDP, and represents the largest form of household wealth, estimated at nearly 70 percent.

However, slower economic growth, the COVID-19 lockdowns, and a drying up of credit to property developers put a sudden stop to the hot housing market. New construction starts fell by 2 percent in 2020 from the previous year, 11 percent in 2021, and 39 percent in 2022. Meanwhile, local government revenue from land sales has gone from more than 40 percent prior to 2021 to 37 percent in 2022 (He 2023).

The liquidity squeeze, initiated by China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping, late in 2020—to stem speculation in housing and excessive leverage (borrowing) by developers—has led to defaults, most of which have been on offshore debt. Of the 50 developers with the most dollar‐denominated bonds issued in Hong Kong, two‐thirds have defaulted on interest payments. Consequently, the market value of those bonds has largely evaporated, losing nearly 90 percent of their value ($136 billion) over the last two years (Wilkins 2023).

The Fall of China’s Largest Developers

Two of China’s largest developers, both private, face possible liquidation. Evergrande and Country Garden have both defaulted on dollar bonds and have liabilities that have grown far beyond their assets. In December 2021, Evergrande failed to pay two dollar‐bond coupons. It is the most indebted developer in China, with liabilities of nearly $330 billion, including $20 billion of offshore debt.

Evergrande chairman Hu Ka‐yan has been detained for possible financial crimes, and his company faces liquidation if it cannot come up with an acceptable restructuring plan for its offshore debt by December 4 (Ao and Yu 2023).

Financial regulations prohibit Evergrande from issuing new bonds, as it is already overleveraged, and its future looks dismal. Its financial reports for 2021 and 2022 came under scrutiny by Prism, a small accounting firm Evergrande hired in January. Upon inspection, Prism could not verify the accuracy of those reports. Moreover, it concluded that, for the first half of this year, there were too many uncertainties to issue a conclusive earnings report. This lack of transparency is endemic in China’s market socialist economy.

Country Garden, which has about $11 billion in dollar‐denominated bonds, missed making a $15.4 million interest payment on its 6.15 percent dollar bond, which was due on September 17. The 30‐day grace period has now ended and the company is in default. The market price of its 6.15 percent note has tanked to about 5 cents on the dollar. Consequently, a cross‐payment default on other dollar bonds seems likely unless Country Garden can come up with an acceptable restructuring plan (Tobin 2023).

Another large developer, China Vanke, has seen the value of its dollar bonds fall sharply following Country Garden’s default. Vanke’s Hong Kong‐listed shares have fallen by 50 percent this year as sales have slumped. Monthly contracted sales reached a high of 100 billion yuan in 2021, but are now around 30 billion yuan.

The Sources of China’s Housing Crisis

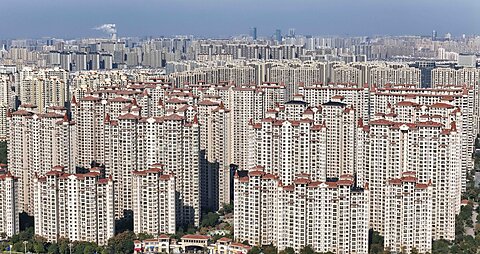

Debt‐fueled development, the lack of investment alternatives for households in a socialist market economy, a thin social safety net, and government policies that helped support the housing sector all combined to create a housing bubble prior to 2020. It is estimated that 96 percent of urban households own at least one house or apartment.

As housing demand increased and prices rose, the widespread expectation was that prices would continue to rise. That expectation was dramatically changed with Xi Jinping’s decision to impose new regulations to stem speculation.

Xi’s Three Red Lines

In August 2020, regulations called the “Three Red Lines” were enacted that required property developers to keep their liabilities (debt) at less than 70 percent of their assets; maintain a debt‐to‐equity ratio of less than 100 percent; and a ratio of cash to short‐term debt of at least 100 percent. Banks were also heavily constrained in making loans to developers. The result was a collapse of the housing bubble as credit dried up to overleveraged developers. In September 2023, sales at China’s 100 largest developers fell by 29 percent from a year ago, with Country Garden’s sales falling 81 percent (Fung and Yoon 2023).

Slower Economic Growth

China largely escaped the global financial crisis (2007–09) by boosting domestic demand to counter the loss of exports. The housing market was an important component of China’s policy to stimulate the economy. However, with slower economic growth—due to the pandemic, inefficient state‐owned enterprises, Xi Jinping’s deviation from market‐based development, the aging of the population, financial repression, and the lack of capital freedom (i.e., the free flow of capital and a free market in ideas)—China’s future development faces many challenges.

Price Supports Prevent Markets from Eliminating the Excess Supply of Housing

In a free market, an excess supply of housing would be eliminated by allowing the price of housing to fall until a new equilibrium is reached at which the quantity supplied and demanded are equal. China’s adherence to market socialism has steered it toward using price supports to prevent decreases in demand (i.e., a leftward shift in the demand curve) from lowering prices to clear the market. Figure 1 shows that by putting a floor under the price of housing (at P1), an excess supply emerges when demand falls. The price of housing must fall to P2 if the market is to clear.

Figure 1: A Price Support Leads to an Excess Supply of Housing

Existing homeowners obviously are against any fall in the price of housing, so there is political pressure to maintain price supports. Yet, policymakers recognize that with nearly 80 million housing units now vacant, prices need to be lowered. Cao Li reports that housing authorities are beginning to allow property developers more freedom to lower prices to eliminate the large excess supply of housing. Creating a freer market in housing by ending price controls would go a long way to help stabilize the housing market.

Financial Repression

China has long suppressed deposit rates and strictly limited investment choices by using capital controls. The lack of a free capital market supported by a genuine rule of law and a trusted, transparent financial system have made private housing one of the best alternatives to park savings. As Wall Street Journal columnist Joseph Sternberg observed, “The financial repression that suppressed interest income from household savings to subsidize lending to politically well‐connected companies helped stoke outsize demand for real estate as an alternative investment.”

Faced with discriminatory policies against foreign firms, including a clampdown on access to official economic data, capital is fleeing China. Much of it is heading for the United States, prompted by a strong dollar, high US bond yields, and trusted institutions. For the first time in 25 years, China has seen overall foreign direct investment turn negative as capital outflows have exceeded inflows by nearly $12 billion in the third quarter this year.

Although China has made some progress in strengthening its financial markets, much remains to be done. Ting Lu, chief economist at Nomura Securities China, argues that “the removal of restrictions and the restoration of market‐driven resource allocation, including the allocation of funds and land resources,” is of “paramount importance.”

Conclusion

China’s housing crisis is part and parcel of market socialism, which puts the power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) above economic and personal freedom. This was made clear at the meeting of the Central Financial Work Conference in October. As Xinhua reported, “The conference stressed the need to adhere to the centralized and unified leadership of the Party Central Committee in financial work”; be “guided by Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”; and follow “Marxist financial theory” in developing “Chinese‐style finance.”

Such vagueness allows plenty of room for the CCP to control key policy variables while paying lip service to the rule of law and open markets. It also creates great uncertainty about the fate of markets and prices in the allocation of credit. If Shanghai is to become a global financial center, China will have to institute a genuine rule of law, adopt transparent accounting standards, end price and capital controls, and move toward a free market in ideas. There is little evidence that Xi will do so.

It is more likely that Beijing will end up bailing out the housing sector, deepening the already significant moral hazard problem, which was created by China’s debt‐driven housing boom and the expectation by lenders that they would be bailed out.