Adam N. Michel

Republicans often invoke the “Laffer Curve” when discussing tax reform. But this mental model often confuses policymakers’ thinking. The most recent confusion came during the last Republican presidential debate when Senator Tim Scott claimed, “What we know is the Laffer Curve still works…the lower the tax, the higher the revenue.”

The Laffer Curve is a useful tool to understand the limits to how high tax rates can go. However, relying too heavily on this model can distort policymakers’ understanding of the benefits of tax cuts. Tax cuts may be worthwhile pursuing, even when they result in less revenue. Sometimes, they are worthwhile because they result in less revenue.

The Laffer Curve

There should be no debate about whether the Laffer Curve works in some situations. The disagreement is over the curve’s parameters.

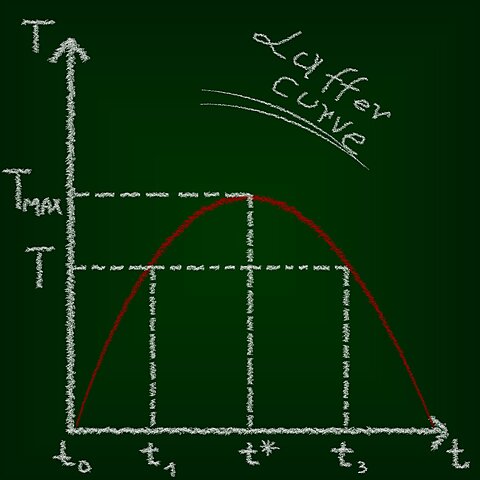

The hypothesis from economist Art Laffer states that a tax will not raise any revenue when the rate is zero or when the rate is 100 percent. The debate is over what happens between the two extremes. Revenue generally rises with the rate until the costs of the tax are so great that revenue begins to fall. That is, the tax base shrinks so much as rates rise that overall revenue falls. At higher tax rates, people work and invest less, substitute more for non‐taxed activities, and increase investment in avoidance and evasion.

Only in some cases does revenue rise as rates fall. This may occur, for example, when a high corporate income tax or capital gains tax rate is cut. However, this is only true if the tax rate is on the wrong side of the peak of the Laffer Curve. The debate over the top of the curve for each tax is important and contested but often complicated by one‐time realization effects, timing shifts, and policy changes to the tax base.

Don’t Think Backward from the Top of the Laffer Curve

If policymakers always reason backward from the top of the Laffer Curve, we might get the impression that the goal of a tax cut is not to set efficient fiscal policy but instead to maximize revenue for the government. Over‐applying the Laffer Curve implies that it only makes sense to cut taxes if the tax rate is on the wrong side of the revenue‐maximizing point. This is obviously false if the goal is limited government and low taxes.

Taxes primarily exist to raise money for governments to spend; thus, spending ultimately sets the long‐run tax rate. Either through direct taxes or inflation (which is an indirect tax), government spending must be paid. Relying on Laffer Curve thinking allows politicians to avoid talking about government spending. If a tax cut always leads to additional revenue, politicians can promise new spending at lower tax rates. This is similar to Democrats claiming large new spending programs can be paid for by taxes on a few very wealthy people. It distracts from reality.

Laffer Curve analysis can also implicitly assume that the revenue from the revenue‐maximizing tax rate results in the appropriate level of government spending. I am not going to resolve the question of welfare‐maximizing government spending levels here, but it seems unlikely that it would be the same as the result of the revenue‐maximizing tax rate.

One reason the Laffer Curve gives policymakers no useful information about the welfare‐maximizing spending level is that the top of the Laffer Curve is highly susceptible to the tax base. If the goal is to maximize revenue extraction, policy changes to what is subject to tax can shift the achievable top rate. For example, broadening the tax base can eliminate planning opportunities and shift the top of the Laffer Curve.

Limited government policymakers should pursue tax and spending cuts to improve economic efficiency and allow individuals to control a larger portion of their earnings. Both goals of an improved economy and lowering the government’s take can be achieved at any tax rate. The economic benefits of tax cuts are largest when rates are high, but this does not negate the benefits of cutting taxes when rates are low.

As structural US federal deficits top $2 trillion, advocates of limited government will need to face the reality that spending ultimately sets the long‐run tax rate, and higher revenues cannot fix our fiscal dilemma. The Laffer Curve is an important concept to keep in mind, but relying on it as orthodoxy can lead to indefensible positions, such as “all tax cuts pay for themselves,” that ultimately undermine the more important project of keeping taxes low and government small.