Patrick G. Eddington

Deadlines tend to focus the mind…except for the House and Senate, which every few years wait until literally the last possible moment to deal with a law that this time around expires at 12:01 a.m. on January 1, 2024.

In this case, the law in question is Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Section 702 involves the interception of communications of “foreign intelligence” interest carried on the global telecommunications network and its related infrastructure.

Last month, a bipartisan group of House and Senate members introduced the Government Surveillance Reform Act. The GSRA would, among other things, extend the Section 702 program for four years but require a probable cause‐based warrant to access the communications of Americans acquired under the program.

Yesterday, a separate bipartisan group of House members introduced the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act (PLEWSA), whose lead author is the extremely controversial Rep. Andy Biggs (R‑AZ). Biggs has emerged as one of the most consistent and harsh critics of the Section 702 program, and his bill, like the GSRA, would impose a probable cause‐based warrant requirement for the communications of Americans. Both bills would also apply the same requirement to government efforts to acquire data on Americans from third parties such as data brokers.

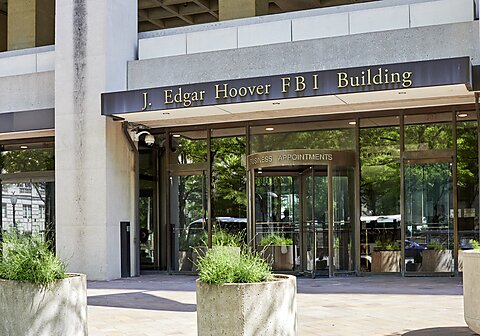

The bipartisan momentum behind these dueling legislative proposals is driven by the execrable record of surveillance abuse racked up by the Section 702 program and its masters—the FBI and NSA—over the last 15 years. Not surprisingly, national security state bureaucrats are fighting back.

The same day Biggs and his colleagues introduced their Section 702 reform bill, Punchbowl News reported that officials at the Justice Department and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) sent a letter to key Senate leaders on the Intelligence and Judiciary Committees claiming, among other things, that a lapse in Section 702 authority would “inject tremendous uncertainty and risk, endangering the IC’s ability to gain valuable intelligence.”

As I pointed out recently in the Orange County Register, that statement is false. During the Clinton administration, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) ran a program under Executive Order 12333 that appears to have been nearly identical to the “upstream” (or internet backbone) portion of current FISA Section 702 collection.

The reality is that the FBI and NSA simply hate having to abide by the Fourth Amendment’s individualized, particularized probable cause‐based warrant requirement.

What they’ve never been able to credibly explain is why that standard—which governs criminal proceedings in conventional Article III courts every day in this country—is impossible to meet in the national security context. The truth is that it is indeed not only possible but absolutely necessary if the Fourth Amendment is to truly have any consistent meaning and effect.

At present, the House and Senate are scheduled to leave DC by December 15—sixteen days before Section 702 is set to expire. Which reform proposal will become law, if any, is at this point anybody’s guess.