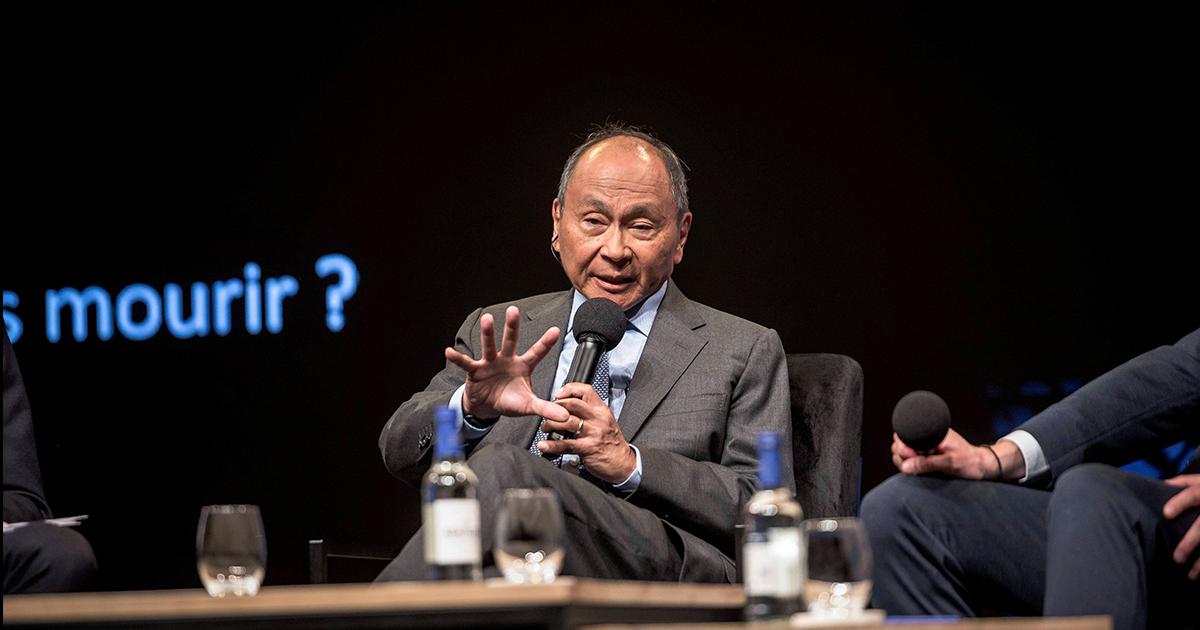

Last week, a video clip of Francis Fukuyama went viral. In the clip, the political scientist called freedom of speech and a marketplace of ideas “18th century notions that really have been belied (or shown to be false) by a lot of what’s happened in recent decades.”

Fukuyama then reflects on how a censorship regime could be enacted in the United States.

But the question then becomes, how do you actually regulate content that you think is noxious, harmful, and the like—and do it in a way that’s consistent with the First Amendment? Now, I think you can push the boundaries a bit because the First Amendment does not allow you to say anything you want. But among liberal democracies, our First Amendment law is among the most expansive of any developed democracy.

And you could imagine a future world in which we kind of pull that back and we say no, we’re going to have a law closer to that of Germany where we can designate—the government can designate something as hate speech and then prevent the dissemination of that. But the question then is, politically, how are you going to get there?

Putting aside the fact that the censorship regime Fukuyama is talking about is already here, it’s important to consider the admission behind his words.

Francis Fukuyama is often associated with the neoconservative movement. And that’s for good reason. He was active in the neoconservative Project for a New American Century and helped lead the push for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. But he later turned against the war and renounced neoconservatism, so he can perhaps better be understood as an intellectual proxy for the Washington establishment.

Fukuyama is best known for his 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. The book argues that liberal democracy represents the endpoint of humanity’s ideological evolution and the final form of government because of its defeat of fascism and socialism and its supposed lack of inner contradictions.

If there was ever a time when this idea would resonate, it was 1992. The Soviet Union was gone, and the US government, fresh off its sound defeat of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, was the most powerful single entity in history.

But at the same time, an entirely new medium for information was quickly emerging. In 1996, a software engineer named Dave Winer decided to host his newsletter on the World Wide Web. The result was the first web log, or blog. He called it DaveNet. As blogs began to catch on, writers could reach their readers directly without filters, editors, or space constraints.

It is hard to understate the effect of this development. But it’s best explained by Martin Gurri in his 2014 book The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium. Gurri posits that throughout human history “information has not grown incrementally… but has expanded in great pulses or waves which sweep over the human landscape and leave little untouched.”

According to Gurri, the first information wave came with the invention of writing. The second was set off by the development of alphabets. These waves gave rise to governments and societies led by literate bureaucratic and priestly castes. The third wave came with the invention of the printing press. Suddenly, the ancien régime’s monopoly on information was shattered. The result was sweeping political change—most notably the Protestant Reformation and the American and French Revolutions.

Central to Gurri’s thesis is the idea that these revolutions did not come about because of a sudden change in the public’s sentiments but because abrupt changes in the information space allowed sentiments that were already there to spread and develop outside of the ruling classes’ control.

The fourth wave came with the adoption of broadcast media—radio and television—during the twentieth century. While this wave was certainly disruptive, the government’s early takeover of the airwaves made it easier for the political class to retain control over the information space.

But the same could not be said of the fifth wave—the digital revolution. Only two years after the launch of DaveNet, another blog, the Drudge Report, would go around the establishment press and break the story that got Bill Clinton impeached.

Ten years later, as yet another financial crisis gripped the country, the internet allowed true grassroots opposition movements to organize and spread—Occupy Wall Street on the left and the Tea Party on the right. It also allowed candidates like Ron Paul to run popular campaigns critical of the Washington establishment.

The internet didn’t just allow people to see and hear dissenting views; it allowed them to see that those views were popular.

And because of that, from the Arab Spring to the passage of Brexit, the weakening of political control over the information space began leading to real change across the world. But in the United States, after Donald Trump won the White House, the political class woke up to what was happening. And they decided to do something about it.

At first it was Russian disinformation, then hateful domestic extremists, and later covid skeptics. The establishment has used whatever boogieman or strawman they thought could scare the public into accepting more political control over the online space. Which brings us back to Fukuyama.

In a sense, he’s right. It was a lot easier for the Washington establishment to act as though they were supportive of freedom of speech and the free exchange of ideas when they controlled the information space. But now that the internet has partially rolled back their control, these ideas have been “belied” in their eyes.

For those like Fukuyama, who want the Washington establishment to keep up its ever-escalating interventionism at home and abroad—funded by unsustainable debt and inflation—the digital revolution is cause for concern. But for those of us who understand that our economic, geopolitical, and cultural issues require radical change, it’s a reason to have hope.