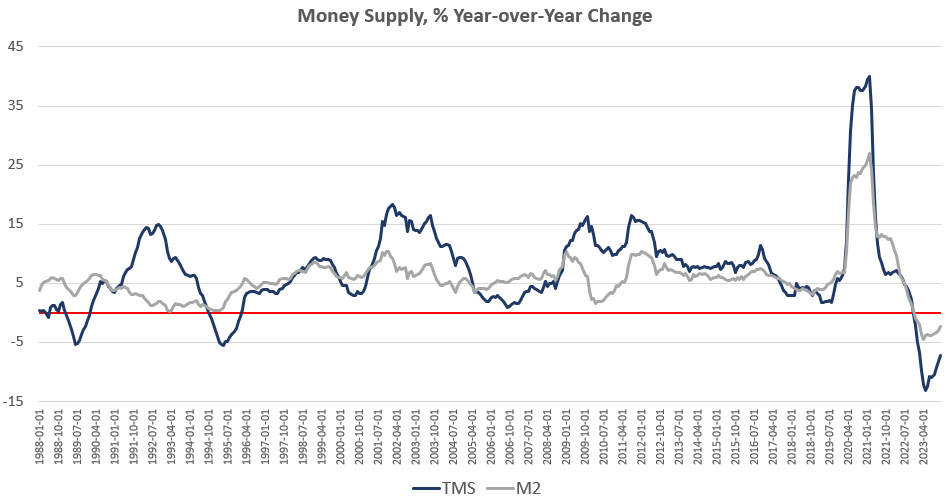

Money supply growth fell again in December, remaining deep in negative territory after turning negative in November 2022 for the first time in twenty-eight years. December’s drop continues a steep downward trend from the unprecedented highs experienced during much of the past two years.

Since April 2021, money supply growth has slowed quickly, and since late 2022, we’ve been seeing the money supply repeatedly contract, year over year. The last time the year-over-year (YOY) change in the money supply slipped into negative territory was in November 1994. At that time, negative growth continued for fifteen months, finally turning positive again in January 1996.

Money-supply growth has now been negative for fourteen months in a row. During December 2023, the downturn continued as YOY growth in the money supply was at –7.32 percent. That’s up slightly from November’s rate of decline which was of –8.36 percent, and was far below December 2022’s rate of –2.2 percent. With negative growth now lasting more than a year and coming in below negative five percent for the past twelve months, money-supply contraction is the largest we’ve seen since the Great Depression. Prior to this year, at no other point for at least sixty years has the money supply fallen by more than 6 percent (YoY) in any month.

The money supply metric used here—the “true,” or Rothbard-Salerno, money supply measure (TMS)—is the metric developed by Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno, and is designed to provide a better measure of money supply fluctuations than M2. (The Mises Institute now offers regular updates on this metric and its growth.)

In recent months, M2 growth rates have followed a similar course to TMS growth rates, although TMS has fallen faster than M2. In December 2023, the M2 growth rate was –2.35 percent. That’s down from November’s growth rate of –2.99 percent. December 2023’s growth rate was also down from December 2022’s rate of 0.98 percent.

Money supply growth can often be a helpful measure of economic activity and an indicator of coming recessions. During periods of economic boom, money supply tends to grow quickly as commercial banks make more loans. Recessions, on the other hand, tend to be preceded by slowing rates of money supply growth.

It should be noted that the money supply does not need to actually contract to signal a recession. As shown by Ludwig von Mises, recessions are often preceded by a mere slowing in money supply growth. But the drop into negative territory we’ve seen in recent months does help illustrate just how far and how rapidly money supply growth has fallen. That is generally a red flag for economic growth and employment.

The fact that the money supply is shrinking at all is remarkable because the money supply in modern times almost never gets smaller. The money supply has now fallen by approximately $2.8 trillion (or 12.8 percent) since the peak in April 2022. Proportionally, the drop in money supply since 2022 is the largest fall we’ve seen since the Depression. (Rothbard estimates that in the lead-up to the Great Depression, the money supply fell by 12 percent from its peak of $73 billion in mid-1929 to $64 billion at the end of 1932.)

In spite of this recent drop in total money supply, the trend in money-supply remains well above what existed during the twenty-year period from 1989 to 2009. To return to this trend, the money supply would have to drop another $3 trillion or so—or 15 percent—down to a total below $15 trillion. Moreover, as of December, total money supply was still up 33 percent (or $4.7 trillion) since January 2020.

Since 2009, the TMS money supply is now up by more than 187 percent. (M2 has grown by 145 percent in that period.) Out of the current money supply of $19 trillion, $4.6 trillion—or 24 percent—of that has been created since January 2020. Since 2009, $12.2 trillion of the current money supply has been created. In other words, nearly two-thirds of the total existing money supply have been created just in the past thirteen years.

With these kinds of totals, a ten-percent drop only puts a small dent in the huge edifice of newly created money. The US economy still faces a very large monetary overhang from the past several years, and this is partly why after eighteen months of slowing money-supply growth, we are only now starting to see a slowdown in the labor market. (For example, job openings have fallen 19 percent over the past year, but have not yet returned to pre-covid levels.) The inflationary boom has not yet ended. Moreover, even thought year-over-year comparisons remain starkly negative, the total money supply has been largely unchanged on a month-to-month basis over the past six months. Specifically, the total TMS money supply rose slightly to $19 trillion in July 2023, and has been nearly flat since then, hovering around $18.9 trillion. From November to December 2023, the TMS measure rose a slight 0.3 percent from $18.9 trillion to $19.0 trillion.

These aggregate numbers obscure many important details of where liquidity is falling, and where it is rising. For example Daniel Lacalle has shown some parts of the economy are entering a bust period while other parts see a continued boom. Put another way, the drop in the money supply over the past year has affected different parts of the economy differently. Lacalle describes the current situation as one of a “private sector recession” or a recession in the productive economy. This is to be contrasted with the continuing boom in government spending and government contractors. The sizable increases in GDP we’ve seen in recent quarters have been driven largely by government spending and job growth in government jobs. When it comes to the government sector, and those industries that benefit directly from government spending, liquidity has not reflected the overall declines we’ve seen in the money supply. As Lacalle explained here at mises.org last month, sizable drops in the money supply have nonetheless been repeatedly mitigated by behind-the-scenes efforts at the Fed to make sure that liquidity continues to move into large banks. Even as some sectors of the economy are facing a deflationary bust, the central bank is careful to make sure the politically-connected financial sector is still flush with cash.

(Nonetheless, the overall monetary slowdown has been sufficient to considerably weaken the economy by some measures. The Philadelphia Fed’s manufacturing index is in recession territory. The Leading Indicators index keeps looking worse. The yield curve points to recession. Temp jobs were down, year-over-year, which often indicates approaching recession. Business bankruptcies surged 58 percent in 2023.)

These efforts to keep the government sector and its cronies within arms reach of easy money can now be seen in the fact the month-over-month change in money supply has flatlined in recent months. This, combined with a slowing in the rate of increase in price inflation has led to calls for the Federal Reserve to once again embrace aggressively expansionist monetary policy. Thanks in part to continued signs of strength in the job market, however, the Fed insists that it does not plan to cut rates in the near future. At this point—given that the money supply has now flattened—a Fed effort to further force down interest rates would accelerate CPI growth once again. In other words, if the Fed reverses course now, prices will only spiral upward.

It didn’t have to be this way, but ordinary people are now paying the price for a decade of easy money cheered by Wall Street and the profligates in Washington. The only way to put the economy on a more stable long-term path is for the Fed to stop intervening to keep pumping liquidity to the regime and its allies. That would mean a return to a falling money supply and popping of economic bubbles. But it also lays the groundwork for a real economy—i.e., an economy not built on endless bubbles—built by saving and investment rather than spending made possible by artificially low interest rates and easy money.