Thomas A. Berry, Brent Skorup, and Christopher Barnewolt

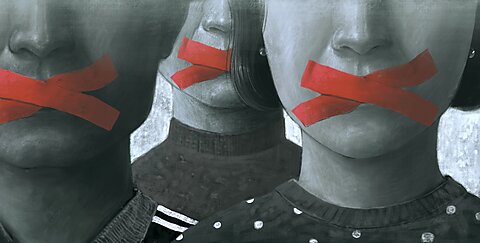

Americans pride themselves on their freedom to criticize the government. Indeed, there is widespread agreement that the First Amendment was added to the Constitution to protect the right of Americans to criticize the conduct of government officials. But for over fifty years, the Securities and Exchange Commission has wielded an immense power to silence the speech of its potential critics: The SEC will not settle a regulatory investigation with someone unless that person agrees to never deny the SEC’s accusations. This “no-admit-no-deny” policy has come to be known as the SEC Gag Rule.

Since its inception in 1972, this Gag Rule has prohibited hundreds of companies and their employees from denying SEC accusations, under the threat of renewed investigation and prosecution. Merely “creating the impression” that the SEC’s charges lacked merit violates the Gag Rule.

While the SEC insists a defendant’s submission to the Gag Rule is always voluntary, this claim is laughable on its face. The SEC is a powerful arm of the federal government with a multi-billion-dollar budget. Few defendants have the resources to defend themselves against a lengthy SEC investigation or lawsuit. Consequently, nearly all defendants agree to settle. Yet after settlement, the SEC’s accusations stand as the last word on the matter as defendants—even those who have done nothing unlawful—must remain silent for life.

The SEC’s Gag Rule means that the government’s side of the story will be the only side of the story the public ever gets to hear.

Thomas Joseph Powell is one of those people silenced by a “voluntary” settlement agreement with the SEC. He, and several others in his position, have sued to restore their First Amendment right to criticize SEC officials and actions. The Cato Institute filed an amicus brief with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Powell v. SEC, urging it to find that the SEC Gag Rule is unconstitutional.

While there are many constitutional problems with the Gag Rule, our brief focuses on two important points. First, we explain that the Gag Rule is a content-based restriction on speech, which under existing First Amendment doctrine must be subject to strict scrutiny. This means that to be constitutional, the restriction must further a compelling governmental interest and be narrowly tailored to achieve that interest. The Gag Rule fails both requirements. The government’s asserted interest—protecting “confidence” in the SEC—is not compelling. And the Gag Rule is not narrowly tailored, as the SEC has many other, less coercive options open to it.

Second, we point out that the Gag Rule violates the unconstitutional conditions doctrine. This doctrine holds that the government may not deny a governmental benefit to a person as punishment for his exercising a constitutional right. As the Ninth Circuit has recognized, giving the government free rein to grant benefits only if a person agrees to forfeit a constitutional right invites the government to abuse its power and erode constitutional protections. For this reason, any alleged “waiver” of constitutional rights—like the right to criticize a regulator—must be carefully scrutinized by the courts to ensure that it is not intended to chill such rights.

The Ninth Circuit should follow its precedent and the Supreme Court’s, declare the SEC’s policy unconstitutional, and enjoin the SEC from enforcing the Gag Rule against Thomas Powell and many others.