Chris Edwards, Marc Joffe, and Krit Chanwong

Without reforms, exploding federal debt will generate a major economic crisis. Technically, the solution to the problem is simple (cut spending), but there is no consensus on what political approach or legal mechanisms are needed to avert the coming crisis.

What can we learn from state governments about controlling debt? We should be able to learn something because debt levels vary widely, as do unfunded liabilities for state worker pensions and other post-employment benefits (OPEB).

For each state, the map shows the sum of state bond debt, unfunded pensions, and unfunded OPEB as a percentage of state gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022. All three types of liability impose risks and costs on future taxpayers.

The data are from Truth in Accounting and include state-level liabilities, but not local liabilities.

The differences between the lowest and highest states are huge. The lowest-liability states—Arizona, Idaho, Nebraska, Tennessee, Utah, Wisconsin, and Wyoming—owe less than 3 percent of GDP. The highest-liability states—Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, and Vermont—owe more than 20 percent of GDP.

Most states use a variety of legal mechanisms to limit bond debt, including limits on debt outstanding, debt servicing costs, and debt issuance. However, there are also large differences in unfunded pension and OPEB obligations between the states, which are not controlled by the rules on bond debt.

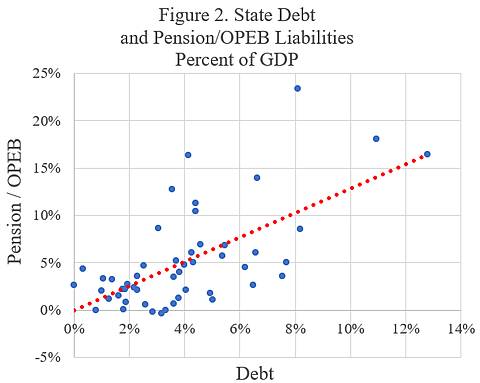

Furthermore, there are similar patterns across the states for debt, pension liabilities, and OPEB liabilities. For example, New Jersey is far above average for all three types of liability, while Nebraska is far below average for all three types. Figure 2 shows the strong statistical correlation between debt on the horizontal axis and the sum of unfunded pensions and OPEB on the vertical axis. Each dot is a state.

The three dots in the top-right are New Jersey, Connecticut, and Hawaii. Those states are much higher for all three types of liability, while Nebraska is near zero for all three types. When thinking about how to tackle exploding federal debt, we should look to budgeting practices in states like Nebraska, not New Jersey.

We don’t know all the reasons for the large liability differences between the states, but political party does seem to play a role. Figure 3 compares the sum of the three types of state liability to the percent of seats in each state’s legislature that are held by Republicans. States with more Republicans tend to have lower liabilities as a percentage of GDP.

However, party is only one of many factors. Note, for example, that at the 35 percent Republican legislator level, state liabilities range from 3.9 percent (in Nevada) to 29 percent (in Connecticut).

In sum, state differences in debt and unfunded pension and OPEB are large. Understanding the causes of these differences may help us tackle the rising debt threat from the legislators of both parties in Washington, DC.