Jack Solowey

When thinking of tech antitrust, the Biden administration’s quixotic campaign against the likes of Meta, Google, and Amazon probably comes to mind. But in addition to suits against big-name Internet platforms, the Justice Department filed an antitrust case this fall against a decidedly more retro network: Visa.

According to the September 24, 2024 complaint, Visa’s debit card network being “everywhere you want to be” is cause for concern because, the DOJ alleges, the company maintains its US market leadership (over 60 percent of debit payments) through anti-competitive contracts with banks, merchants, and fintech companies. In the words of the DOJ, Visa “uses its dominance to limit the growth of existing competitors and to deter others from developing new and innovative alternatives.”

Sorry, but paeans to the virtues of competition and innovation in payment technology are rich coming from the federal government. This same government has all-too-merrily erected and aggressively enforced its own barriers to payment alternatives. What’s more, the government’s own misguided interventions in the debit card market are arguably at the root of the alleged activity it now complains about.

The course of the DOJ’s case remains to be seen. But regardless of its outcome, the federal government’s approach to competition in payments requires significant course correction. If the government truly wants to unleash payment competition and fintech innovation in the United States, it should start by rolling back its campaign against both.

The Debit Card Market

The DOJ’s first broad claim is that Visa hampers competition from other debit card providers through exclusionary contracts with issuing banks (who issue debit cards on Visa’s network) and acquirers (who accept payments for merchants). Yet even if one took the DOJ’s allegations at face value, the federal government’s distortionary policy interventions likely would be an underlying cause.

Indeed, the DOJ argues that Visa’s alleged contracting practices are a response to a portion of Dodd-Frank known as the Durbin Amendment. The Durbin Amendment, along with its implementing regulation from the Federal Reserve (Regulation II), is perhaps best known for capping the processing fees (interchange fees) that debit card-issuing banks can charge to merchants/acquirers accepting debit payments. In addition to fee caps, the Durbin Amendment also requires debit cards to support payments routed over at least two different networks. (The Credit Card Competition Act—a new bill by Senator Durbin (D‑IL)—would apply similar requirements to the credit card industry.)

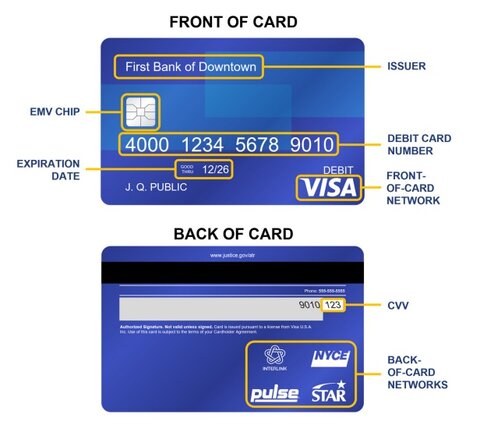

To understand the Durbin Amendment’s routing requirement, it helps to look at a physical debit card. In addition to your bank’s (or credit union’s) logo, the front of your debit card will likely have the logo of the payment card network (e.g., Visa or Mastercard) that your bank contracts with to exchange transaction information with your merchant’s bank. Following the Durbin Amendment, your debit card also would be required to support payments over an additional network that’s unaffiliated with the primary “front-of-card” provider. If you flip over your debit card, you may see the logo of one of these additional networks (e.g., STAR, Pulse, NYCE, etc.).

According to the DOJ, Visa consigns these “back-of-card” networks to a less-than-second-class status by writing contracts with issuers and acquirers that restrict and disincentivize routing more than a de minimis portion of transactions through the alternatives.

At first glance, the Durbin Amendment’s back-of-card network requirement may appear to be a pro-competitive policy. But good intentions notwithstanding, the policy does little to improve (and likely harms) consumer welfare due to its fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the payment card market.

A payment card network is what’s known as a two-sided market. This means that for a network to be useful, it must have a critical mass of two types of users: consumers and merchants. Without enough of either, the network is far less valuable to the other: think Uber with either too few drivers or riders. As the Supreme Court put it—when finding in favor of American Express in a 2018 antitrust case—a payment card is “more valuable to cardholders when more merchants accept it, and is more valuable to merchants when more cardholders use it.”

Achieving that critical mass of consumers and merchants is no small feat. It involves investing in secure and effective technology, as well as marketing to reach users on both sides of the market. The problem with the Durbin Amendment’s mandate is that it allows the back-of-card network to freeride on the investments and brand equity of the front-of-card network.

For example, a front-of-card network may earn its place on the card in a consumer’s wallet through various features (like robust security) that won the trust of the consumer’s bank, which, in turn, won the trust of the consumer. That network will seek to recoup the cost of those features with a commensurate merchant/acquirer fee model. Under the Durbin Amendment’s vision, however, a back-of-card network could get the benefit of being in the consumer’s wallet—the chance to win a merchant’s routing business—without necessarily offering the same features as the front-of-card network. Indeed, if the back-of-card network wants that routing business, there’s a good chance it may try to undercut the front-of-card network with a different strategy, such as fewer features but lower merchant/acquirer fees.

There’d be nothing wrong about that tradeoff if that’s what the consumer and her bank had freely chosen. But the Durbin Amendment ignores the full weight of their actual choice by mandating that a second-choice network (at best) gets to ride alongside the consumer’s first-choice network in her wallet. Carrying second-place competitors to unearned first-place finishes by fiat is an inferior substitute for real competition.

What’s more, the Durbin Amendment appears to be an overall policy failure, resulting in additional bank fees for consumers. As Ronald Bird writes in Regulation:

The preponderance of the post-regulation literature suggests that the 2011 regulation did not achieve its goals of lowering merchant fees and increasing debit card usage. Instead, the regulation increased checking account fees, increased minimum deposit requirements for free checking, increased ATM fees, reduced or even eliminated consumer rewards programs, and reduced the overall level and growth trend of debit card use.

While much of this counterproductive result is attributable to the Durbin Amendment’s interchange fee caps, as Julian Morris and Todd Zywicki point out, similar effects also stem from back-of-card network mandates. Examining data from credit unions and community banks that were subject to back-of-card mandates but not fee caps, Morris and Zywicki conclude that “the Durbin Amendment’s routing requirements have reduced interchange-fee income and raised costs for exempt banks and credit unions, which have responded by increasing fees and reducing benefits (such as debit-card rewards).”

There’s a reasonable argument, therefore, that a payment card network finding a workaround to the poor policy prescriptions and distortionary interventions of the Durbin Amendment would be, on net, consumer welfare enhancing.

Fintech Competition

The DOJ’s second broad claim against Visa is that it suppresses competition from fintech alternatives (like Apple Pay, Cash App, and PayPal) by conditioning those apps’ compatibility with Visa cards on the providers limiting their use and development of non-Visa payment rails.

Ironically, in this domain, the government’s argument recognizes the value of networks and nature of two-sided markets. Specifically, the DOJ contemplates how fintech providers could leverage their established relationships with consumers and merchants to attempt to scale their own interbank payment arrangement that disintermediates Visa.

This wouldn’t be the first time the government has been able to grok payment market fundamentals when convenient to its own arguments. For example, in 1998, the Federal Reserve published a report concluding that the Fed should remain a provider of check processing and automated clearinghouse (ACH) services. At the time, the Fed itself, which competed with private ACH providers, handled 80 percent of commercial interbank ACH transactions. In the Fed’s view, however, its dominant market position was not a cause for concern because “with or without the Federal Reserve, the [ACH] industry is likely to be dominated by one or two large players, much like the market for credit card processing” (emphasis added).

The Fed had a point that ACH and payment card markets, with relatively high fixed costs and low marginal costs, will tend to have fewer, larger providers—but query why 80 percent market share should be no cause for concern when the Fed has it, but 60+ percent is alarming in the case of Visa?

Moreover, the government putting on its concerned face when it comes to alleged impediments to fintech alternatives takes a lot of chutzpah. The government itself is the undisputed titleholder in impeding fintech alternatives. In just the past few years, the federal government has sought to impose new compliance burdens on fintech providers without a risk-based justification, ramped up enforcement actions targeting fintech-bank relationships, denied state-chartered depository institutions lawful access to Federal Reserve master accounts, waged a relentless campaign of regulation by enforcement against crypto projects, and driven banks serving crypto clients into corners and out of business—to name just a few of its barriers to payment innovation.

One of the richest government hypocrisies can be seen in light of the DOJ’s concern that we’re missing out on fintech alternatives from big tech companies like Apple. Because when Facebook, now Meta, sought to participate in the development of a payment stablecoin (Libra, later Diem) accessible via a digital wallet linked to Facebook’s and WhatsApp’s user networks (among other wallets), the government lost its mind. Against that backdrop, the Biden Administration put forward a proposal to restrict stablecoin issuance to insured depository institutions (i.e., banks) and, thus, take it out of the hands of non-bank tech platforms.

If our government wants to identify obstacles to new payment tools, it should first look in the mirror.

Conclusion

The federal government is a massive bureaucracy with many, many departments—each with a different mandate and agenda. Yet the federal government’s overall resistance to payment alternatives has been such that when any federal agency claims to be defending fintech innovation, the appropriate rejoinder is “Yeah, if only.” Hauling leading private payment providers like Visa into court may garner headlines. But if the government is serious about payment alternatives it should first get to work removing all of the stumbling blocks—from regulation by enforcement to discretionary pressure campaigns—that Washington places in their way.