Mike Fox

As a former public defender, I know better than to confess to a crime. But recently, I found myself in a situation that perfectly illustrates how easily an ordinary person can stumble into legal trouble, even with the best intentions. My crime: walking my dog along the West Front Lawn of the US Capitol on Memorial Day.

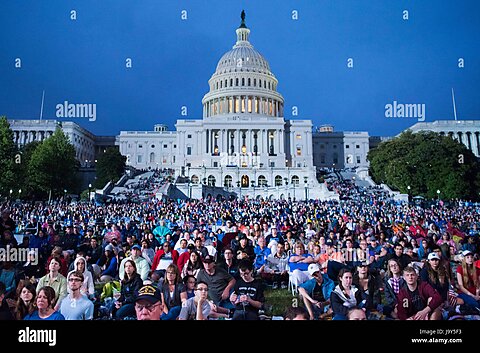

What started as a pleasant stroll quickly turned into a perplexing predicament. The day before was the National Memorial Day Concert. On Memorial Day itself, with the concert over and most of the equipment cleared, it appeared the area had been reopened. So, I walked right in.

It wasn’t until I was well inside the perimeter, with no obvious way out, that I observed the signs indicating that the area was closed pursuant to 18 U.S. Code § 1752: Restricted Building or Grounds. It appeared that the barricades containing these signs where I entered had been knocked down and pushed aside—perhaps by the workers breaking down the equipment—leading me to believe the area was accessible. I had no idea I was breaking the law.

The bad news: A harmless infraction like this could land someone up to a year in jail. The good news for me, however, lies in a crucial legal detail: 18 U.S. Code § 1752 includes an intent element, or mens rea. Specifically, the statute requires that one “knowingly enter or remain.” My defense is clear: I had no notice—hence no intent to violate the law.

My experience immediately brought to mind the plight of Michelino Sunseri, whose case I’ve been involved with over the past few months. Like me, Sunseri had no actual notice that he was committing a crime. But here’s the critical difference: the regulation he was charged under was never passed by Congress and—even worse—contained no intent element. This means that Sunseri didn’t have the benefit of the doubt I might have.

Sunseri’s case highlights a troubling conflict. On one side, fortunately, the Department of the Interior is now attempting to follow President Trump’s Executive Order aimed at combating overcriminalization, specifically the proliferation of criminalization by regulation, which Sunseri fell victim to. On the other hand, you have federal prosecutors who, like Ariel Calmes and Nicole Romine, prioritize persecuting decent people over seeking justice. Their relentless pursuit of Sunseri is emblematic of the massive disconnect between the letter and spirit of the law and the unchecked power of unaccountable prosecutors. This fosters an environment where individuals can be blindsided by regulations they had no reasonable way of knowing about, and without the crucial safeguard of the government having to prove intent.

Thankfully, there’s traction in Congress to confront these issues. Last week, the House Judiciary Committee advanced two significant pieces of legislation: the Count the Crimes to Cut Act and the Mens Rea Reform Act. These bills offer real hope for ordinary people like Sunseri. They aim to rein in the ever-expanding list of federal crimes and, critically, ensure that individuals can’t be prosecuted for simply not knowing about an obscure rule or statute. They underscore the fundamental principle that to be found guilty, one should actually have known they were doing something wrong.

As we move forward, these reforms are essential to protecting everyday citizens from the unintended consequences of an ever-growing body of laws and the potential overreach of prosecutorial power. Because no one should face jail time for an innocent walk in the park or run up a mountain.