According to a new report from the federal government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics last Friday, the US economy added 353,000 jobs for the month of January while the unemployment rate held at 3.7%. CNN news was sure to tell us that this was a “shockingly good jobs report” and it “shows America’s economy is booming.”

At this point, many of us who follow these numbers have become accustomed to the routine: the BLS reports “blowout” jobs numbers each month, and the legacy media dutifully reports that the jobs growth is astoundingly good, proving all is well in the economy.

The media rarely reports on any other economic indicators with nearly as much enthusiasm. The monthly jobs report—well, one specific statistic within it—has become something of a proxy for the state of the economy overall.

There are a couple of problems with this approach, of course. The first is that the jobs numbers—a trailing indicator of economic growth (or decline) are repeatedly contradicted by at least half a dozen other economic indicators. Many of these other indicators are, unlike jobs numbers, leading indicators, and are more useful if we’re actually looking for some hints at what is in store.

If we take a larger look around, we find this: The Philadelphia Fed’s manufacturing index is in recession territory. The same is true of the Richmond Fed’s manufacturing survey. The Leading Indicators index keeps looking worse. The yield curve points to recession. Business bankruptcies surged 58 percent in 2023. Net savings turned negative for only the second time in decades. The economic growth we see is being fueled by the biggest deficits since covid.

But, there’s also the problem that the jobs report itself isn’t so impressive once we look beyond the headline establishment survey jobs data.

The first fly in the ointment of this “shockingly good jobs report” is the results we see from the household survey. The household survey is a survey of actual people who are asked if they are employed. The establishment survey, on the other hand, is a survey only of large employers and the total number of jobs—i.e., not job holders.

So, if we look at the household survey, we find that there were actually job losses in January. While the establishment survey showed an increase of a whopping 353,000 jobs, the household survey showed a loss of 31,000 employed persons. Moreover, January was the second month in a row for job losses in the household survey. In December, the report showed a loss of 683,000 employed persons. That was the biggest loss since the covid collapse.

How does this square with the huge jobs blowouts in the establishment survey? Part of it can be explained by the fact that the establishment survey does not distinguish between full-time and part-time workers or jobs. It’s entirely possible that there are more jobs being added in the economy—it’s just that many of them are going to people holding multiple jobs, and many of those jobs are part time. So, if the economy is filling up with fewer people holding two or more part time jobs, that registers as “blowout” jobs growth. The reality, however, is that fewer people are employed.

Moreover, the household survey also tells us that job growth among the employed was mostly driven by part-time jobs in January. According to the survey, growth in part-time jobs totaled 96,000 while full-time job growth went negative, with a loss of 63,000.

Meanwhile, government jobs in January totaled more than 20 percent of all new year-over-year job growth. Outside of covid, we haven’t seen those sorts of numbers since late 2007 as the economy was nearing recession.

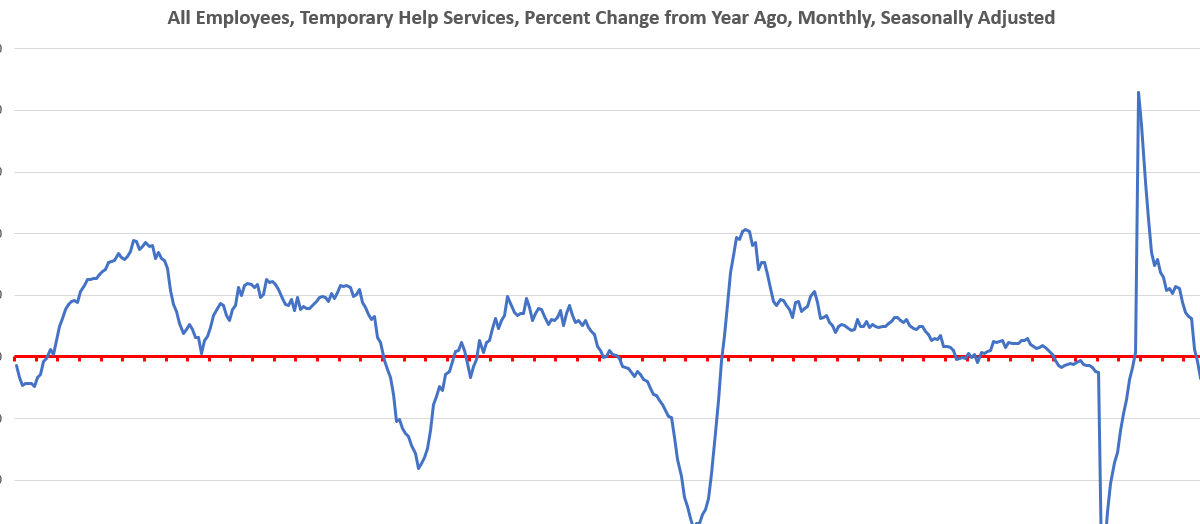

And then there is the growth rate of temp jobs. That remained in negative territory last month for the fifteenth month in a row. As the graph shows, drops in temp jobs over the past thirty years has been a clear indicator of an approaching recession.

Finally, we can look at real wage growth. Legacy media sources were careful to crow about how January showed real growth in average earnings. Specifically, average earnings (adjusted to the CPI) increased 1.7 percent, year over year. In a vacuum, that might be a great number. However, workers are still recovering from a 25-month period of falling real average earnings. That meant earnings on average in 2022 were below 2019 earnings, and working only started to come out of that hole in 2023. Indeed, if we look at real earnings growth since February 2020—the last month before the covid lockdowns—we find that earning increased a mere 1.53 percent—or 51 cents—over that 47-month period. During that same time, home prices increased 46 percent (according to Fannie and Freddie). It’s easy to see why housing affordable is now at some of the worst levels we’ve seen in decades.

In spite of all this, however, American consumers of television news are fed a steady diet of good news about the economy in which each month brings a new “shockingly good” or “robust” jobs report. Even more questionable is the practice of treating the jobs report as if it’s an index for the overall economy. However, the jobs report is only something to brag about if one’s definition of a strong jobs economy is one in which fewer people have jobs, full-time jobs are disappearing, and government jobs are a growing component of overall job growth.

When we view these numbers in light of declining manufacturing, more bankruptcies, recessionary leading indicators, and negative net savings, we might suspect that the economy is headed for some turbulence ahead.

The Federal Reserve, however, has encouraged the laser-like focus on current jobs data because the FOMC has claimed to be basing much of its economic planning on jobs growth. Approximately every month, for example, Jerome Powell addresses the press with a prepared statement about the Fed’s policy being this or that while using jobs numbers to justify its current policy. At least, that is the public face the Fed puts on. The Fed wants the public to believe the Fed is “data driven” and is fine-tuning—another term for centrally planning—the economy based on fine detective work from Fed economists. That’s the story they tell. The reality is something different, and the Fed is making its decisions based on political expediency. Polls have shown, however, that the average voter tends to base his opinion of the economy on the jobs situation “right now.” So, lo and behold, the Fed says it is doing the same.

The economy doesn’t work that way, though, and if we want to understand what direction the economy is heading in, we have to rely on sound theory rather than what some Federal bean counters say happened last month.